Scientists have unearthed fossils of a prehistoric forest dating back to 380 million years ago that could have been the cause of a massive reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) levels hundreds of millions of years ago.

The researchers, from Cardiff University in Wales and the University of Southampton in England, wrote about their findings in the academic journal Geology.

Prof. John Marshall and Dr. Chris Berry found the fossil forests, with their tree stumps preserved in place, in Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean between mainland Norway and the North Pole.

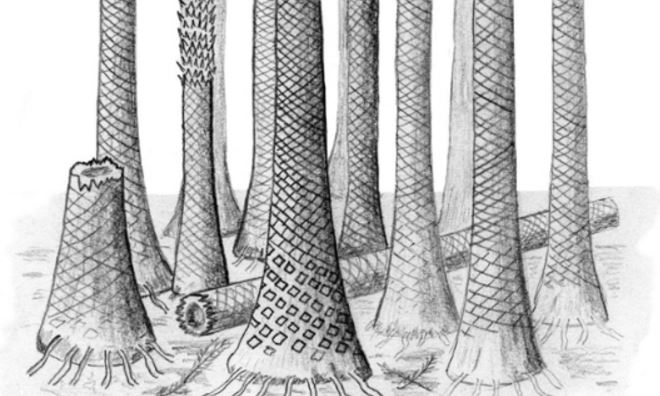

Can these prehistoric forest fossils help explain why CO2 levels dropped so dramatically hundreds of millions of years ago? (Image: Cardiff University)

Can these prehistoric forest fossils help explain why CO2 levels dropped so dramatically hundreds of millions of years ago? (Image: Cardiff University)

Dr. Berry, who works at Cardiff University’s School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, identified and described them.

Prof. Marshall, from the University of Southampton’s National Oceanography Centre, accurately dated the forests to 380 million years ago.

Why did CO2 levels drop so dramatically?

The forests, which grew close to the equator during the late Devonian period, may provide clues to help explain the 15-fold reduction levels in atmospheric CO2 around that time.

Scientists theorize that during the Devonian period (420 to 360 million years ago), there was a dramatic decline in atmospheric CO2, caused largely by a change in vegetation from small plants to the first large forest trees.

Through photosynthesis, forests are believed to have pulled CO2 out of the atmosphere.

While initially the emergence of large trees absorbed more of the sun’s radiation, eventually Earth’s surface temperatures also declined dramatically to levels similar to those we experience today, because of lower levels of atmospheric CO2.

Most CO2 drop likely from tropical forests

Because of the elevated temperatures and large amounts of precipitation (rainfall) on the equator, the equatorial forests probably contributed to most of the CO2 drawdown.

Around that time, Svalbard was located on the equator, before the tectonic plate shifted north by about 80° to its position today in the Arctic Ocean.

Dr. Berry said:

“These fossil forests shows us what the vegetation and landscape were like on the equator 380 million years ago, as the first trees were beginning to appear on the Earth.”

The scientists found that the Svalbard forests were formed mainly of lycopod trees, better known for growing several millions of years later in coal swamps that eventually turned into coal deposits, like those in South Wales.

Dr. Berry and colleagues reported that the forests were super dense, with tiny gaps – about 20 cm (7.9 inches) – between each tree. Trees probably averaged about 4 metres (13 feet) in height.

Dr. Berry said:

“During the Devonian Period, it is widely believed that there was a huge drop in the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, from 15 times the present amount to something approaching current levels.”

“The evolution of tree-sized vegetation is the most likely cause of this dramatic drop in carbon dioxide because the plants were absorbing carbon dioxide through photosynthesis to build their tissues, and also through the process of forming soils.”

In an Abstract in the journal, the authors concluded:

“This high-tree-density tropical vegetation may have promoted rapid weathering of soils, and hence enhanced carbon dioxide drawdown, when compared with other contemporary and more high-latitude forests.”

Citation: “Lycopsid forests in the early Late Devonian paleoequatorial zone of Svalbard,” Christopher M. Berry and John E.A. Marshall. Geology. DOI: 10.1130/G37000.1.