Ravens are capable of paranoia, even when the threat is not visible, just like humans. They are aware that unseen others may be spying on them, that is, even if they cannot see other rival ravens – if they know there is a way for them to be seen, they are aware of this and their behaviour changes.

If a raven is guarding its food hoard and can hear but not see other ravens, and there is an open peephole, it will guard it more carefully. However, if you cover that peephole, they become more relaxed and less worried, because they seem to know it is much less likely that they are being watched, i.e. the threat is lower.

One of the oldest philosophical puzzles people have talked about is ‘What sets us apart from other animals?’ A common answer is that we are the only creatures capable of appreciating that others also have minds of their own.

The raven’s behavior changes if it thinks there is a chance of being watched by rivals. (Image: www.uh.edu)

The raven’s behavior changes if it thinks there is a chance of being watched by rivals. (Image: www.uh.edu)

Ravens capable of abstract thought

In a new study, researchers from the Universities of Vienna in Austria and Houston in Texas, USA, wrote in the academic journal Nature Communications that ravens – birds often mentioned in several cultures as a symbol of wisdom and intelligence – share at least some of our ability to think abstractly about other minds, and adapt how they behave according to their perception of others.

Thomas Bugnyar and Stephan A. Reber, from the University of Vienna’s Department of Cognitive Biology; and Cameron Buckner, from the University of Houston’s Department of Philosophy, found that ravens carefully guarded food against discovery when they heard the sound of other ravens when a nearby peephole was open, even if no other bird was visible.

They did not show the same concern when the researchers closed the peephole, even though they could still hear the raven sounds – this means they knew for sure they were not being watched.

Cameron Buckner, assistant professor of philosophy, says he and his colleagues’ findings shed new light on science’s understanding of Theory of Mind, the ability of one being, such as a human, to attribute mental states – including vision – to others.

Virtually all Theory of Mind studies have been done with chimps and other species closely linked to humans.

Previous studies had rivals looking directly at them

However, while those studies have suggested that animals have the capacity to understand what others see – which gives them an advantage when competing for food, for example – the animals being observed were able to see the eyes of their rivals.

Put simply, this is the only study where the test subjects (ravens) could not see the eyes of others – they had no ‘gaze cues’.

The raven won’t approach its cache if it believes there is a chance it is being observed. It does not need ‘gaze cues’ – it is capable of abstract thought. (Image: Wikipedia)

The raven won’t approach its cache if it believes there is a chance it is being observed. It does not need ‘gaze cues’ – it is capable of abstract thought. (Image: Wikipedia)

Skeptics may say that the animals in these experiments may have been responding just to these surface cues, without really appreciating what others see.

“Thus,” Buckner and colleagues write to describe the previous state of the research “it still remains an open question whether any non-human animal can attribute the concept ‘seeing’ without relying on behavioral cues.”

Buckner, whose research concentrates on animal cognition, said the researchers avoided that concern in this latest study by using only open peepholes and sounds to indicate that a competitor might be present or nearby, with the ravens never able to physically see another raven in the context of the experiment.

Ravens and humans follow similar social phases

Buckner says ravens are a good subject for the study, because in spite of their evident evolutionary divergence from humans, similar to people, their social lives go through many distinct phases.

In particular, ravens frequently defend territories in stable breeding pairs as adults, but as adolescents they tend to have a much more fluid lifestyle.

Buckner said:

“There is a time when who is in the pack, who’s a friend, who’s an enemy can change very rapidly. There are not many other species that demonstrate as much social flexibility. Ravens cooperate well. They can compete well. They maintain long-term, monogamous relationships.”Fcocial

“This all makes them a good place to look for social cognition, because similar social pressures might have driven the evolution of similarly advanced cognitive capacities in very different species.”

Ravens pair up for life. In many ways, their social phases are similar to humans’. (Image: itsnature.org)

Ravens pair up for life. In many ways, their social phases are similar to humans’. (Image: itsnature.org)

Ravens behave differently when they think they’re being watched

For ravens, being able to cache (hoard) food is important, and previous studies had demonstrated that their behaviour changes when they perceive a rival or competitor is watching.

For example, when a raven is being watched, it hides food more rapidly and is less likely to return to a previously made cache, both which risk revealing the location of a cache to a possible competitor. If it does not think it is being watched, it’ll spend more time on the task.

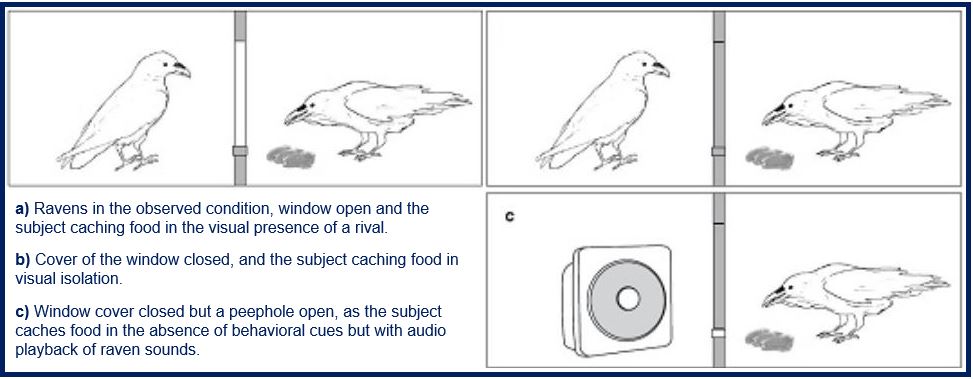

In this study there were two rooms, both connected by windows, which could be covered or opened, and by peepholes, which could be closed or open.

The researchers trained the ravens to peer through the peepholes to observe a human experimenter making caches in the next room.

In the final phase of the experiment, both the windows were covered but the peephole was open. A hidden speaker emitted the sound of a raven rival, but no other bird was visible. The subjects (ravens) still cached as though they were being observed.

For ravens ‘seeing’ may be more that a direct view

The authors explained:

“We show that ravens … can generalize from their own experience using the peephole as a pilferer and predict that audible competitors could potentially see their caches (through the peephole). Consequently, we argue that they represent ‘seeing’ in a way that cannot be reduced to the tracking of gaze cues.”

Their findings offer vital data into several different arenas, Buckner said, including evidence that ravens are potentially excellent animal models in research involving social cognition.

Buckner added that the study also offers new evidence about the capacities involved in Theory of Mind and abstract thinking. “It could change our perception of human uniqueness, that we share some of that ability not just with chimpanzees and closely related species but also with a very different species,” he said.

The authors would like to see which other animals have the same capacity for the kind of abstraction the ravens were capable of in the peephole test, “especially humans, since we don’t know when this ability emerges in childhood.”

Buckner said:

“Finding that Theory of Mind is present in birds would require us to give up a popular story as to what makes humans special. But completing this evolutionary and developmental picture will bring us much closer to figuring out what’s really unique about the human mind.”

Citation: “Ravens attribute visual access to unseen competitors,” Thomas Bugnyar, Stephan A. Reber & Cameron Buckner. Nature Communications 7, Article number: 10506. DOI:10.1038/ncomms10506.

Video – Raven’s acute visual memory

In this video, Sir David Attenbrorough shows how acute a Raven’s visual memory is.