Snakes lost their legs when they evolved and started living and hunting in burrows, a team of scientists from Scotland and the United States says, after analyzing a 90-million-year old fossilized skull. Many snakes today still live and hunt in burrows.

Researchers from the University of Edinburgh and the American Museum of Natural History explained in the academic journal Science Advances that according to comparisons between CT scans of the fossil, snakes did not lose their limbs in order to be able to live in the sea, as had been suggested previously.

Dr. Hongyu Yi, from Edinburgh University’s School of GeoSciences, and Dr. Mark Norell, of the American Museum of Natural History, used CT scans to examine the inner ear of Dinilysia patagonica, a 2-metre long reptile closely linked to snakes today.

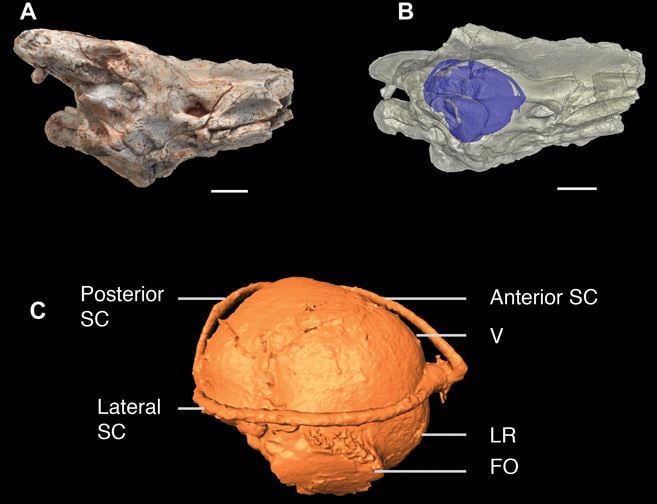

(A) D. patagonica’s braincase, showing the right otic region in lateral view. (B) X-ray CT model of MACN-RN 1014 – the inner ear is highlighted in blue. (C) Bony inner ear of D. patagonica. FO, foramen ovale; LR, lagenar recess; SC, semicircular canal; V, vestibule. Scale bars, 5 mm. (Image: Science Advances)

(A) D. patagonica’s braincase, showing the right otic region in lateral view. (B) X-ray CT model of MACN-RN 1014 – the inner ear is highlighted in blue. (C) Bony inner ear of D. patagonica. FO, foramen ovale; LR, lagenar recess; SC, semicircular canal; V, vestibule. Scale bars, 5 mm. (Image: Science Advances)

The bony canals and cavities of its inner ear, like those of modern burrowing snakes, controlled the animal’s hearing and balance.

Detailed 3-D models

Drs. Yi and Norell created 3-D virtual models to compare the inner ear of modern lizards and snakes with those of fossils.

The scientists found a distinctive structure inside the inner ear of the animals that actively burrow, which probably helps them spot prey and predators. This structure was not found in modern snakes that live above ground or in water.

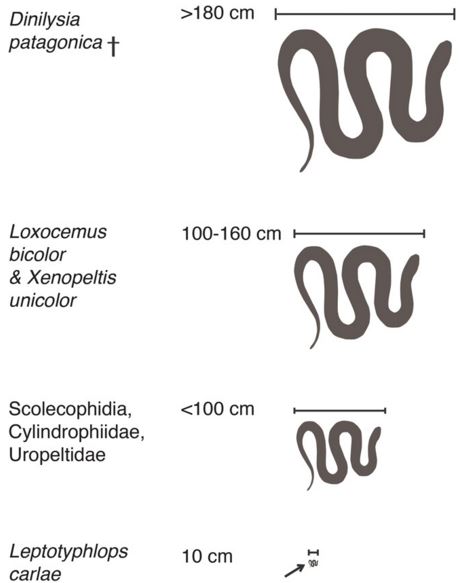

The researchers say their findings help scientists fill gaps in the story of the evolution of snakes. Dinilysia patagonica is the largest burrowing snake ever known, the authors confirmed.

Their findings also offer clues about the hypothetical species from which all modern snakes descended, which was probably a burrower.

Total body size of D. patagonica compared to snakes today. Loxocemus bicolor is the largest existing burrowing snake, growing up to 160 cm. Leptotyphlops carlae is the smallest existing snake. (Image: Science Advances)

Total body size of D. patagonica compared to snakes today. Loxocemus bicolor is the largest existing burrowing snake, growing up to 160 cm. Leptotyphlops carlae is the smallest existing snake. (Image: Science Advances)

Dr. Hongyu Yi said:

“How snakes lost their legs has long been a mystery to scientists, but it seems that this happened when their ancestors became adept at burrowing. The inner ears of fossils can reveal a remarkable amount of information, and are very useful when the exterior of fossils are too damaged or fragile to examine.”

Dr. Norell said:

“This discovery would not have been possible a decade ago – CT scanning has revolutionised how we can study ancient animals. We hope similar studies can shed light on the evolution of more species, including lizards, crocodiles and turtles.”

The study was supported by The Royal Society.

Citation: “The burrowing origin of modern snakes,” Hongyu Yi and Mark A. Norell. Science Advances, Vol. 1, no. 10, e1500743. 27 Nov 2015. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500743.