Storks are either not migrating at all or flying much shorter distances than they used to. They conserve energy by staying in places made by humans were they can feed, such as rubbish dumps and fish farms, says a research team led by Dr. Andrea Flack, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Germany.

Research has shown that storks that spend the winter feeding on rubbish dumps rather than migrating are more likely to survive the cold season. The stork is one of an ever-increasing number of migratory birds that have altered their behavior due to human influences, the researchers wrote in the journal Science Advances.

All storks in Europe used to migrate south for the winter, that is, until recently. Now, many of them are either flying shorter distances to feed on rubbish dumps and other food sources in or near urban areas, or staying put for the whole winter.

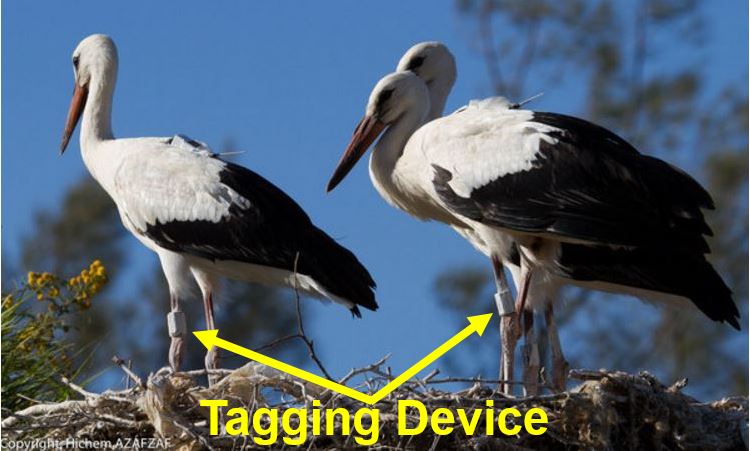

Young white storks with tagging devices fitted so that the researchers could track them. (Image: orn.mpg.de)

Young white storks with tagging devices fitted so that the researchers could track them. (Image: orn.mpg.de)

Flying distances determine how much energy is used up

The annual migratory flight can range from a few tens to thousands of kilometres, creating unique energetic requirements for each bird species and journey.

Even within the same species, migration costs can vary considerably because of several opportunities now available to birds.

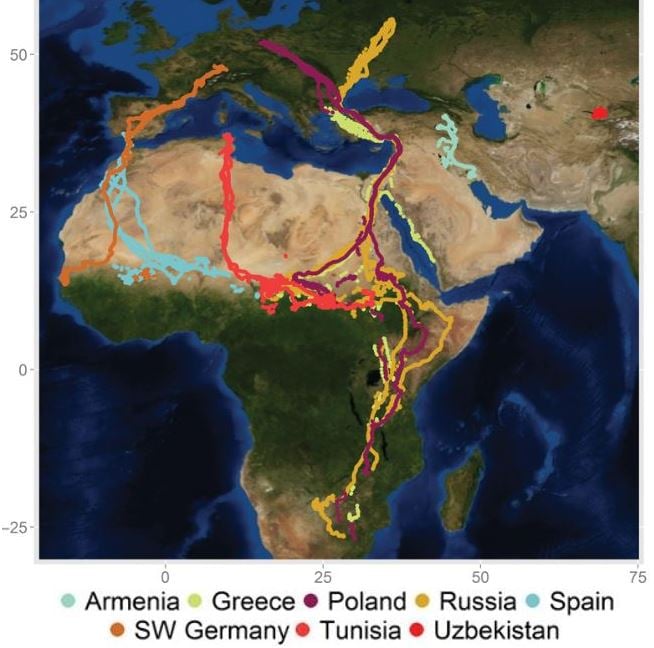

The authors, from Germany, Spain, Russia, Armenia, Greece, Poland, Tunisia, Israel and South Africa, say their study uncovered the huge migratory variations among young white storks that had hatched in eight countries – Tunisia, Armenia, Spain, Greece, Poland, Russia, Germany, and Uzbekista.

A total of seventy young storks were fitted with GPS devices so that the scientists could track them during their first migration.

White storks breed in Europe, north-west Africa and western Asia.

Not only did the young storks differ in the various geographic locations where they spent their winters, their diverse migration patterns also affected how much energy each one used up flying during the first months of their life.

Migration paths of 62 young white storks tracked with GPS/GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications) (8 birds died before migrating). (Image: Science Advances)

Migration paths of 62 young white storks tracked with GPS/GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications) (8 birds died before migrating). (Image: Science Advances)

Storks closer to people flew less

Storks in areas with a high human population density used up less energy because of their shorter daily foraging trips, shorter migrations trips, or no migration at all.

The authors found that storks from Greece, Poland and Russia continued their traditional migratory route of flying as far south as South Africa.

However, birds from Germany, Tunisia and Spain only flew as far north of the Sahara, while storks from Armenia traveled only a short distance. In Uzbekistan, they gave up migrating altogether.

According to the researchers, the majority of the young storks that remained north of the Sahara survived on food they found on rubbish dumps. This meant they were able to feed themselves without having to expend the extra energy required for the long-distance flight.

With so much food available in rubbish dumps, many white storks are not bothering to migrate.

With so much food available in rubbish dumps, many white storks are not bothering to migrate.

The birds in Uzbekistan probably got their food from the fish farms, and suppressed their usual migratory habit of spending the winter in Pakistan or Afghanistan.

“Those that stay north of the Sahara seem to have advantages from feeding on these landfill sites in Morocco. For a white stork it’s a good place; they find a lot of food there. But of course it’s a risk; one wrong food and they’re dead.”

In an Abstract in the journal, the authors wrote:

“Overwintering in areas with higher human population reduced the stork’s overall energy expenditure because of shorter daily foraging trips, closer wintering grounds, or a complete suppression of migration.”

“Because migrants can change ecological processes in several distinct communities simultaneously, understanding their life history decisions helps not only to protect migratory species but also to conserve stable ecosystems.”

Citation: “Costs of migratory decisions: A comparison across eight white stork populations,” Andrea Flack, Martin Wikelski, Wolfgang Fiedler, Thabiso M. Mokotjomela, Julio Blas, Ivan Pokrovsky, Michael Kaatz, Maxim Mitropolsky, Karen Aghababyan, Leszek Jerzak, Ioannis Fakriadis, Eleni Makrigianni, Hichem Azafzaf, Claudia Feltrup-Azafzaf, Shay Rotics and Ran Nathan. Science Advances. 22 January 2016. Vol. 2, no. 1, e1500931. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500931.