Thousands of undelivered 17th century letters have been found in a leather trunk in the Netherlands, ranging from an account of the desperation of an unwanted pregnancy, correspondence containing religious tokens, letters with business samples, to examples of how spies sent vital information.

What began with a music historian reading a short brief in a 1938 French journal regarding undelivered 17th century letters in The Hague, the Netherlands, has mushroomed into an international collaboration involving experts from the Universities of Oxford, Groningen and Leiden, Yale, MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), and the Museum voor Communicatie in The Hague.

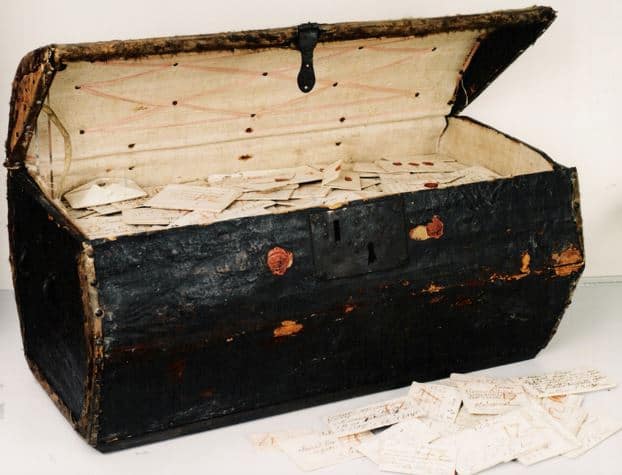

The postmaster’s treasure chest full of undelivered 17th century letters. (Image: Signed, Sealed and Undelivered. Credit: Courtesy of the Museum voor Communicatie)

The postmaster’s treasure chest full of undelivered 17th century letters. (Image: Signed, Sealed and Undelivered. Credit: Courtesy of the Museum voor Communicatie)

A glimpse of life in early modern Europe

According to Yale News, these thousands of undelivered letters paint a vivid picture of what life was like in early modern Europe.

The project, titled ‘Signed, Sealed and Undelivered,’ centers on an archive of letters, all of them undelivered, 2,000 opened and 600 unopened, sent from across Europe to The Hague from 1698 to 1707.

The museum was given these letters in 1926, in the original trunk belonging to Simon de Brienne and his spouse, Maria Germain, two postmasters in The Hague between 1676 and 1707.

It all started with an unrelated investigation carried out by assistant professor of music at Yale, Rebekah Ahrendt, who in 2012 was tracking a theater group that worked in The Hague at the turn of the 18th century.

Prof. Ahrendt found a short notice that described a collection of letters – all undelivered – at the postal museum. It quoted texts within of seven of them.

She did some legwork to find out which museum had the letters and was able to track down its curator.

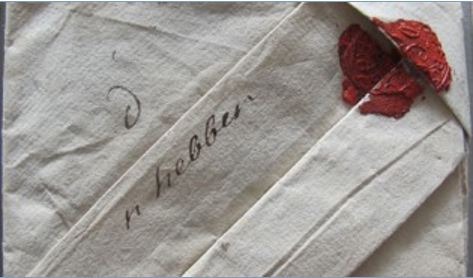

The seal of one of the letters found in the leather trunk. (Image: brienne.org/lettersindex)

The seal of one of the letters found in the leather trunk. (Image: brienne.org/lettersindex)

Thousands of unopened letters in a trunk

Prof. Ahrendt said:

“The letters that were in the trunk were a sort of postal piggybank. It just blew my mind.”

The team working on the ‘Signed, Sealed, and Undelivered’ project include Daniel Starza Smith (Lincoln College, University of Oxford), Nadine Akkerman (University of Leiden), Koos Havelaar (Museum voor Communicatie, The Hague), Jana Dambrogio (Massachusetts Institute of Technology Libraries), David van der Linden (University of Groningen), and Rebekah Ahrendt (Yale University).

Prof. Ahrendt said:

“One of the great things about this collaboration, is that we have the curator of the collection, a professional conservator, and academics, and we can all learn from each other. And this research is right in line with the courses that I already teach.”

The postmasters established the archive in an attempt to make money from their business. In those days, recipients had to pay for any letters they received.

If they were undelivered, the postmasters would hold onto them in the hope that the recipient one day would search for the letter and pay them the delivery fee.

An example of a ‘refused’ love letter. (Image: news.yale.edu. Credit: Museum voor Communicatie)

An example of a ‘refused’ love letter. (Image: news.yale.edu. Credit: Museum voor Communicatie)

The trunk that the letters were stored in had been waterproofed with sealskin.

Our notion of what an archive is ‘challenged’

Prof. Ahrendt said:

“Somehow, these letters managed to survive all these years. This collection challenges our notion of what an archive is because it was never intended to be one. It came together by accident.”

They also found elaborate accounting books in the trunk, which detailed the prices for sending letters over 300 years ago.

Prof. Ahrendt explained:

“We discovered how postal routes and the financial system of that time worked. There is documentation of the point at which you paid a rider or a boatman to transport your post. We learned about the connection between the post office in Hague and the post office in Paris. We even found nasty letters from the Parisian postmaster saying that he hadn’t been paid properly.”

The researchers were amazed at how much correspondence went back and forth at the time. Many of the letters, the team members said, were about broken hearts and themes that one would not speak of out loud.

Some letters had religious tokens tucked in, such as this colored paper dove with the French inscription ‘don de piété (‘gift of piety’), symbolizing the Holy Spirit. (Image: news.yale.edu. Credit: Museum voor Communicatie)

Some letters had religious tokens tucked in, such as this colored paper dove with the French inscription ‘don de piété (‘gift of piety’), symbolizing the Holy Spirit. (Image: news.yale.edu. Credit: Museum voor Communicatie)

Plea on behalf of a pregnant friend

One of the letters was written by a woman on behalf of an opera singer friend. It was addressed to a wealthy merchant in The Hague, and reads:

“I am writing on behalf of your friend and mine and she realized as soon as she left the opera company in The Hague to go to Paris that she had made a terrible mistake. Now she needs your help to come back to The Hague. I could tell you the true cause of her pain, but I think you can guess (the woman was pregnant).”

Prof. Ahrendt said the postmaster’s office would write down why a letter was not delivered. It might be marked ‘dead’ or ‘moved to England’. The one referring to the pregnant opera singer was marked ‘refused’.

Rebekah Ahrendt, assistant professor at the Department of Music at Yale University. (Image:http://brienne.org/debrienneprojectteam)

Rebekah Ahrendt, assistant professor at the Department of Music at Yale University. (Image:http://brienne.org/debrienneprojectteam)

Some of the letters included items tucked inside, such as business samples or religious tokens.

One of the letters – possibly an early example of marketing – contained a sample thread with several different colors, types, and gauges of thread. Each strand was painstakingly pasted with a wax seal onto the page.

Prof. Ahrendt, who was especially interested in the correspondence between musicians, said:

“This archive is truly a cultural history of musicians. I was surprised to learn that musicians traveled so much during that time period.”

“We have so few witnesses to describe what daily life was like for your average musician, and these letters tell of large networks of these musicians traveling frequently. This is completely different from what we previously believed about the history of musicians.”

Unopened letters tell their stories

There were even things to be learned from the unopened letters. Jana Dambrogio has been examining how the senders secured their letters, a method she describes as ‘letterlocking’. Dambrogio’s team are looking for a correlation between the different formats and the letters’ contents.

They found, for example, that if the missive is folded one way, it is probably a love letter, because esthetically, it is more pleasing than secure. One with a fold is likely to be a spy letter, because it is harder to open.

Prof. Ahrendt noted:

“The materials used to secure the unopened letters are just as important as the contents within.”

The research team is looking into different scanning techniques to determine whether they can see inside the letters without having to open them.

Prof. Ahrendt said:

“The next step of our work is to connect the cultural history aspect of the project with science and technology so that we can realize our vision.”

A ‘tape recording’ of languge usage at the time

The letters were written in six languages, which have presented the team with a linguistic challenge.

Many of the letters were written by people who were barely literate. While some of them hired professional letter writers, the majority were written by average people who spelled phonetically in their own dialects.

These letters give us a ‘tape recording’ of how people at the time sounded. In order to understand the contents, the researchers often had to read them out aloud.

In those day, when somebody received a letter, he or should was expected to share their correspondence, so the letters included greetings to family and friends.

Prof. Ahrendt noted:

“This material generated an almost unconscious response in me that I imagine the person 300 years ago – if they had actually received the letter – would have felt.”