Wage transparency reduces the gender pay gap by seven percent, economists from business schools in France, the US, and Denmark have found. Requiring employers to disclose gender segregated wage statistics to reveal differences in male and female pay reduced the pay gap by seven percent in Denmark.

Women’s wages are lower than men’s for the same work in the labor markets of most of the advanced economies. An advanced economy, or developed country is one which has a relatively high GDP per capita and a high HDI score. HDI = Human Development Index.

For every $100 men earn, women in Germany and the UK earn $78.5 and $79 respectively. According to Eurostat, the average across the European Union is $83.8 (women) for every $100 (men).

Trade Unions, policy makers, and academics have been debating the gender pay gap problem for many years. Often, these debates have become heated and intense.

Individuals and organizations have been pushing for legislation that requires employers to make their gender-based wage statistics public. They believe that greater wage transparency subsequently narrows the gender pay gap.

No narrowing of gender pay gap, say opponents

Those who oppose pay transparency have claimed that publishing gender-based wage statistics places a heavy administrative burden on employers. It also violates employee privacy as well as confidentiality.

They add that its effect on narrowing the gender pay gap is either unclear or non-existent.

Transparency does reduce gender pay gap

However, according to new research, pay transparency does help close the gender pay gap.

Researchers in this latest study released a working paper (citation below) that examined the effect of new legislation in Denmark in 2006.

The new legislation required employers with more than 35 workers to publish their gender-specific wage statistics.

The researchers say that the Danish legislative step could be a promising avenue for closing the gender pay gap.

The study

The researchers analyzed data from 2003 to 2008. They focused on employers with 35-to-50 workers. They compared the pay data they had gathered with identical data from a control group of companies with 25-34 workers. The control group consisted of employers of a similar size which did not have to publish this type of data.

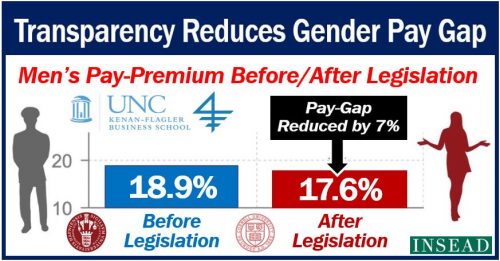

The employers that the researchers had analyzed paid their male workers an 18.9% wage premium before the new legislation came into effect.

After the new law came in, the gender pay gap had declined to 17.6% in about 1,000 Danish companies. In other words, the gender pay gap shrank by 7%.

Daniel Wolfenzon, Professor of Finance and Economics and also Chairman of the Finance Division at Columbia Business School, said:

“What surprised us the most was the way in which this wage gap closed. Women’s wages did not increase at a faster rate in treatment firms as we were expecting.”

“Instead, we find that men’s wages in treatment firms grew slower relative to men’s wages in control firms. As a result, the total wage bill grew slower in firms that were required to report wage segregated statistics.”

Citation

“Do firms respond to gender pay gap disclosure?“ Morten Bennedsen (INSEAD & University of Copenhagen), Elena Simintzi (University of North Carolina Kenan-Flagler Business School), Margarita Tsoutsoura (Cornell University), and Daniel Wolfenzon (Columbia Business School). October 2018. Department of Economics, University of Copenhagen (PDF).