The UK is becoming an ideal wine country that is beginning to compete as an equal with French, Italian, Californian, Australian and Chilean wine producers, says a new study. However, this new land of wine will have a number of weather shocks – downpours, sharp frosts and cold snaps – which could threaten productivity, say researchers from the University of East Anglia.

As British wine producers prepare for what they expect will be a super-bumper 2016 season, an article in the Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research (citation below) reveals that year-to-year climate variability and weather shocks at crucial points during the growing season could leave the whole industry highly vulnerable to the elements.

According to the authors, vogue wine varieties such as Pinot noir and Chardonnay are more susceptible to British climate variability than traditional varieties.

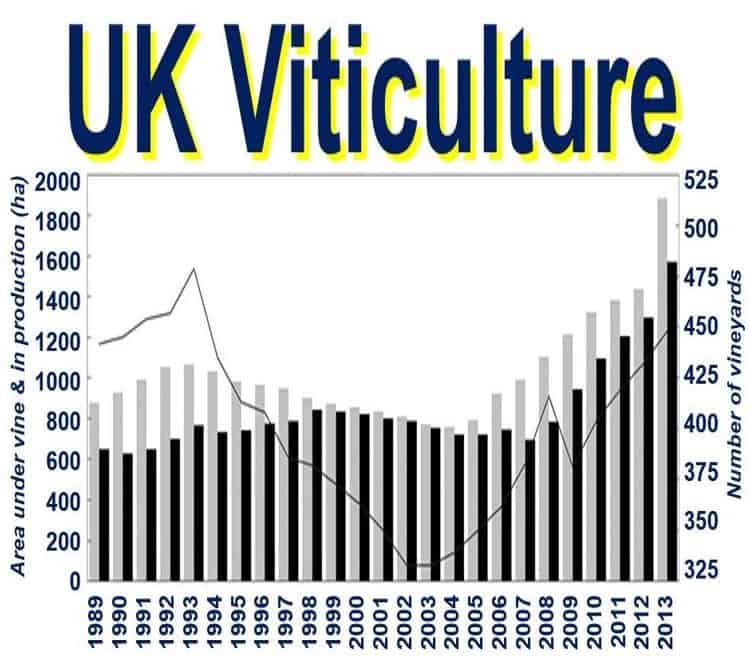

Area under vine in the UK (image), area in production (■), and vineyard numbers (1989–2013) (––), based on data from the Wine Standards Branch of the Food Standards Agency. (Image: onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

Area under vine in the UK (image), area in production (■), and vineyard numbers (1989–2013) (––), based on data from the Wine Standards Branch of the Food Standards Agency. (Image: onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

An English vine growing explosion

English wine production has been booming over the past ten years. The amount of land used for vine growing (viticulture) has risen by 148% – with the equivalent of 2,638 football pitches (1,884 hectares) currently devoted to the wine industry.

Not only has wine production increased significantly, producers have been receiving recognition across the world for their premium quality wines – particularly English Sparkling Wine, which is out-performing other more famous sparkling wine-producing regions.

Alistair Nesbitt, a research student at the University of East Anglia’s School of Environmental Sciences, and colleagues studied Britain’s main grape-growing regions and looked at the relationships between rainfall, temperature, and extreme weather events.

The researchers also surveyed wine producers for their views on the role that climate change might be playing on the success of English wine.

By combining this data, they were able to, for the first time, identify benefits and threats to the industry.

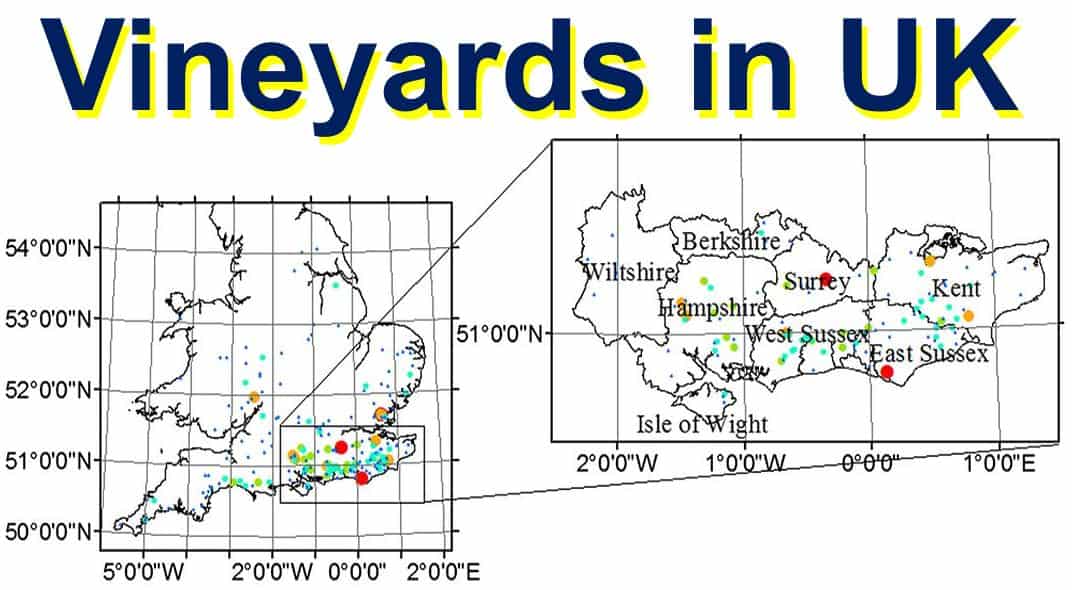

Spatial distribution of vineyards >2 ha in the United Kingdom [2–5 (dark blue), 5–10 (light blue), 10–25 (green), 25–50 (orange), 50–110 (red) ha]. (Image: onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

Spatial distribution of vineyards >2 ha in the United Kingdom [2–5 (dark blue), 5–10 (light blue), 10–25 (green), 25–50 (orange), 50–110 (red) ha]. (Image: onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

UK warming faster than global average

Regarding UK weather, Mr. Nesbitt said:

“The UK has been warming faster than the global average since 1960 and eight of the warmest years in the last century have occurred since 2002. Producers recognised the contribution of climate change to the sectors recent growth, but also expressed concerns about threats posed by changing conditions.”

“We wanted to see whether potential future climate change may make wine-making more viable in the UK by first analysing sensitivity to past climate variability.”

“We found that while average temperatures over the growing season have been above a key minimum threshold for ‘cool-climate’ viticulture for two decades, wine yields vary considerably.”

Key findings from the study

– Rainfall in June is the main weather indicator in explaining year-to-year yield variability in Britain.

– In Britain’s dominant viticultural areas – central-southern and south-eastern England – there has been a non-linear warming during the growing season over the past five decades.

Chapel Down vineyard, in Tenderden, Kent. (Image: englishwineproducers.com)

Chapel Down vineyard, in Tenderden, Kent. (Image: englishwineproducers.com)

– Year-to-year productivity is affected by weather variations and extreme events.

– Frosts are particularly damaging to yields if they occur at crucial times, such as soon after bud-burst in spring.

– Sensitivity to weather variability has increased recently. The researchers say it is because of an increase in vogue wine varieties such as Pinot noir and Chardonnay.

Mr. Nesbitt said:

“Our findings identify threats to the industry, as well as opportunities. High quality wine grapes grow best with an average growing season temperature in the range of 13-21°C. But even within this range, there are other factors at play.”

“Since 1993, the average southern England growing season temperature has consistently been above 13°C and since 1989 there have been 10 years where the temperature was 14°C or higher (up to 2013). This is around the same temperature as the sparkling wine producing region in Champagne during the 1960s, 70s and 80s.”

West Sussex vineyard Nyetimber received the gold medal in the 2014 International Wine Challenge for its 2009 Classic Cuvée. (Image: www.harpers.co.uk)

West Sussex vineyard Nyetimber received the gold medal in the 2014 International Wine Challenge for its 2009 Classic Cuvée. (Image: www.harpers.co.uk)

“However by comparison, UK wine yields are very low. In Champagne, yields can be more than 10,000 litres per hectare, but in the UK, it is around 2,100 on average. While rising average temperatures are important, the impact of short term weather events such as cold snaps, sharp frosts, and downpours will continue to threaten productivity.”

The authors attribute bumper years, 1996, 2006 and 2010, to ideal temperatures and weather conditions – no frosts at critical times, and warm springs and autumns.

Low yielding years – 1997, 2007, 2008 and 2012 – have been attributed to spring frosts, poor summers, low levels of sunlight, wet and cold growing seasons, and cold weather during flowering.

Bodiam Castle Vineyard in East Sussex – managed by Sedlescombe since 1990, which produced the first organic sparkling wine from its 1990 vintage. The English organic wine business is booming. (Image: englishorganicwine.co.uk)

Bodiam Castle Vineyard in East Sussex – managed by Sedlescombe since 1990, which produced the first organic sparkling wine from its 1990 vintage. The English organic wine business is booming. (Image: englishorganicwine.co.uk)

Warmer weather means longer seasons

The researchers found that the months of April and May have become warmer over the past twenty-five years. This is an important time when buds burst and initial shoot growth occurs. Warmer temperatures at this time mean the season starts earlier, and consequently is longer for that year.

However, when just April is warm and May air frost follows, that is bad for yield and wine quality.

Mr. Nesbitt added:

“In June, wet weather, particularly when combined with cool and overcast conditions, can really impact the flowering process, delaying it and reducing the number of berries and young grapes forming on the vines. We saw a correlation between high June rainfall and poor yield across the whole period we studied.”

“A recent change in dominant UK vine varieties has also increased the industry’s sensitivity to weather variability. There has been a drive to produce English sparkling wines such as Chardonnay and Pinot noir – but these grapes are more sensitive to our climate variability.”

“It’s too early to predict what the weather may hold in store for the 2016 growing season, but a warm spring with low frost levels would be the promising start producers are hoping for.”

Citation: “Impact of recent climate change and weather variability on the viability of UK viticulture – combining weather and climate records with producers’ perspectives,” A. Nesbitt, B. Kemp, C. Steele, A. Lovett & S. Dorling. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 31 March 2016. DOI: 10.1111/ajgw.12215.

Video – English wine versus Champagne

As the Government looks to boost UK wine exports, the BBC asks buyers at a Kent vineyard to taste test English sparkling wine, Champagne, and a New Zealand variety.