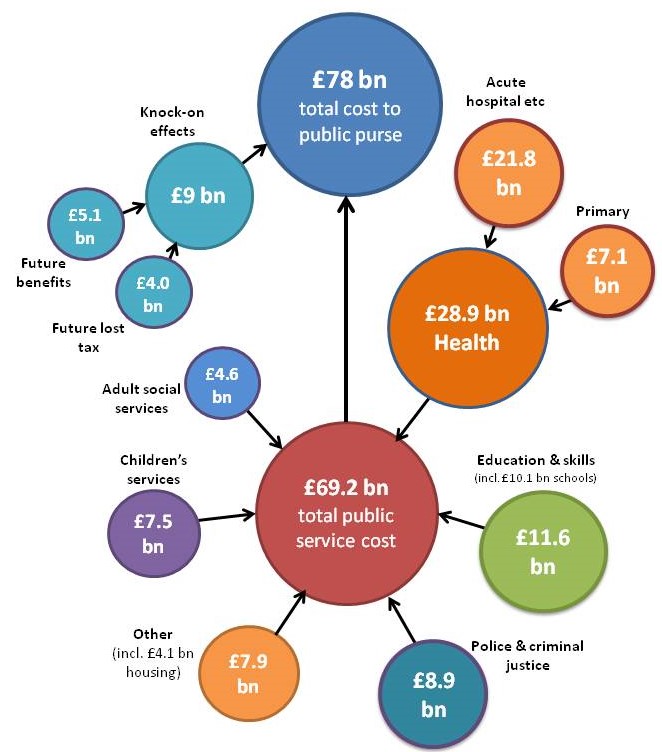

The cost of UK poverty to the public purse is around £78 billion – about £1,200 for every person, and equivalent to 4 percent of UK’s GDP. This figure includes £69 billion for public services and £9 billion due to lost tax revenue and additional spend on benefits to compensate for the effects of poverty.

So conclude researchers from Heriot Watt and Loughborough Universities in a report on UK poverty for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF). Their research highlights the economic benefit of tackling poverty, as opposed to the clear social benefit.

Some of their key findings include:

– £29 billion a year, the cost of 126,000 nurses, goes on treating health conditions associated with poverty

– Higher crime rates in more deprived areas raise criminal justice and police costs by 35 percent (around £9 billion a year)

– £10 billion a year is spent on free school meals and helping disadvantaged pupils via the Pupil Premium

– Children’s social services and early years provision associated with UK poverty cost about £7.5 billion a year

– 26 percent (£4.6 billion a year) of adult social care expenditure is linked to poverty

– £4.1 billion of housing costs are due to UK poverty.

‘Extremely costly to Treasury’

One of the researchers, Professor Donald Hirsch of the Centre for Research in Social Policy at Loughborough University, says it is hard to assess the full cost of poverty, “not least its full scarring effect on those who experience it.”

However, he says the report shows UK poverty has “very large, tangible effects on the public purse.”

“The experience of poverty, for example, makes it more likely that you’ll suffer ill health or that you’ll grow up with poor employment prospects and rely more on the state for your income,” says Prof. Hirsch, adding:

“The very large amounts we spend on the NHS and on benefits means that making a section of the population more likely to need them is extremely costly to the Treasury.”

The researchers estimated the more tangible cost of UK poverty, specifically in terms of impact on the public purse. (Data from JRF Report Counting the Cost of UK Poverty.)

The researchers estimated the more tangible cost of UK poverty, specifically in terms of impact on the public purse. (Data from JRF Report Counting the Cost of UK Poverty.)

‘Level of UK poverty shameful’

Julia Unwin, Chief Executive of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, says:

“The level of poverty in the UK is shameful. This should be a place where everyone can live a decent, secure life. Instead, 13 million people – half of whom are in a working family – are living without enough to meet their needs.”

Unwin says poverty “doesn’t just hold individuals back, it holds back our economy too.” By depriving society of the skills and talents of people whose potential is wasted by it, poverty drags down productivity, curbs economic growth, and reduces tax revenues.

£1 in every £5 of spending on public services is linked to poverty, and much of it is spent on remedying its effects, note the researchers, as they conclude:

“Putting public effort into helping people thrive is ultimately more fruitful than having to spend money picking up the pieces of broken lives.”

Next month, JRF are launching a comprehensive, long-term plan that will propose how individuals, communities, charities, businesses, and Government can work together to solve the problem of UK poverty.

In the emerging economies, poverty refers to people earning less than $1.25 per day. Although poverty exists in the UK and other advanced economies, its definition is not the same.

Video – Income Inequality

Income inequality highlights the gap between the highest and lowest earners in an economy.