The wild tiger, whose population is 97% lower than a century ago, now has a promising future and a real probability of seeing its population double or even triple by 2022, says a team of scientists. However, in order to turn this likelihood into a reality, we have to start taking measures now.

The worldwide population of wild tigers – at fewer than 3,500 individuals – is currently dangerously low, a team of researchers wrote in the journal Science Advances (citation below).

The combination of habitat loss plus poaching could seriously undermine the international target recovery of doubling the global wild tiger population by 2022.

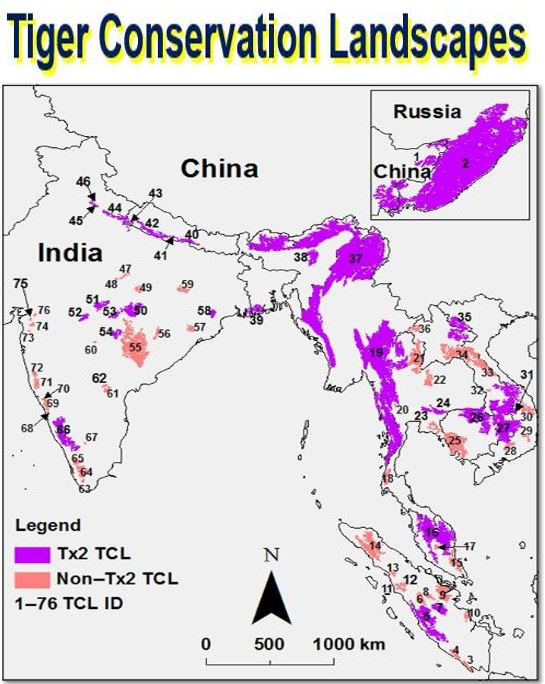

Distribution map of seventy-six Tiger Conservation Landscapes. Tx2 TCLs (n = 29) are landscapes that have the potential to double the wild tiger population by 2022. One Tx2 TCL in the transboundary region of Russia and China is shown in the top-right inset (top right corner). (Image: advances.sciencemag.org)

Distribution map of seventy-six Tiger Conservation Landscapes. Tx2 TCLs (n = 29) are landscapes that have the potential to double the wild tiger population by 2022. One Tx2 TCL in the transboundary region of Russia and China is shown in the top-right inset (top right corner). (Image: advances.sciencemag.org)

A team of scientists from the University of Minnesota, the Biodiversity and Wildlife Solutions Program, Stanford University, the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, the University of Maryland, and the World Resources Institute, used a new satellite-based monitoring system to analyze fourteen years of forest loss data within seventy-six landscapes, ranging in size from 278km2 to 269,983km2 that have been selected for the conservation of wild tigers.

Their analysis provides an update of the tiger-habitat status, and describes new applications of technology to pinpoint precisely where forest loss is taking place in order to stem future habitat loss.

Across the seventy-six landscapes, forest loss was considerably less than had been expected (79,597 ± 22,629 km2, 7.7% of remaining habitat) over the period 2001 to 2014.

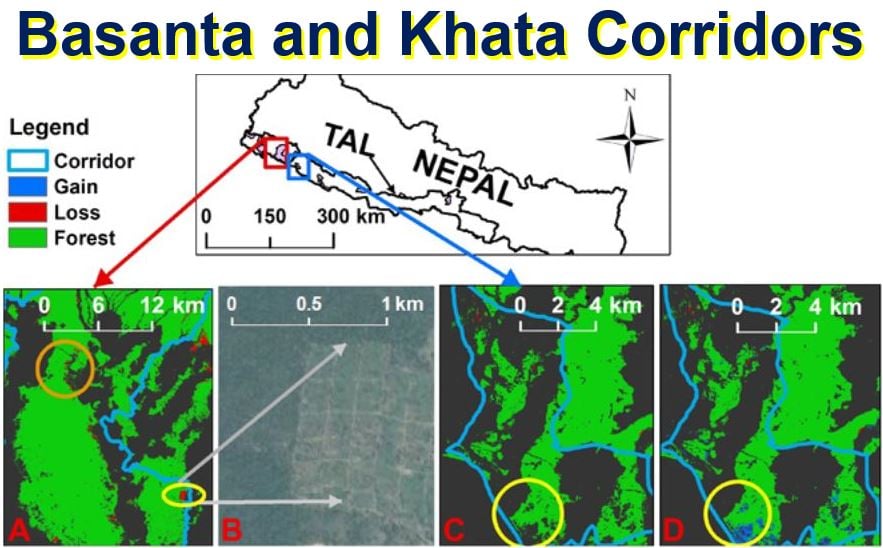

Basanta (A & B) and Khata (C & D) corridors in the Terai Arc Landscape (TAL), Nepal. (Image: advances.sciencemag.org)

Basanta (A & B) and Khata (C & D) corridors in the Terai Arc Landscape (TAL), Nepal. (Image: advances.sciencemag.org)

Of a subset of 29 landscapes deemed most critical for doubling the population of the wild tiger, nineteen showed little change (1.5%), while ten accounted for over 98% (57,392 ± 16,316 km2) of habitat loss.

If we are serious about doubling the tiger population by the year 2022, he must move beyond simply tracking annual changes in habitat.

In an Abstract in the journal, the authors wrote:

“We highlight near- real-time forest monitoring technologies that provide alerts of forest loss at relevant spatial and temporal scales to prevent further erosion.”

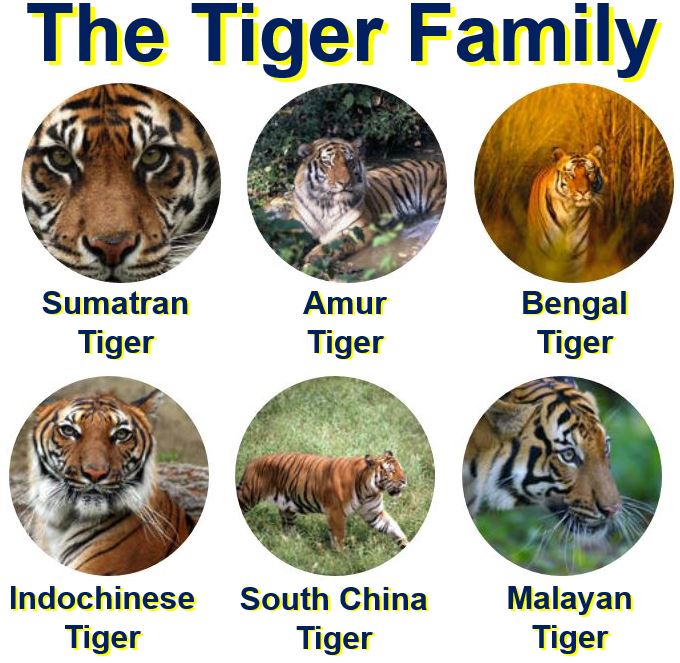

Tigers are one of the most iconic animals on Earth, but they are also one of the most endangered. Despite their popularity in religion, movies and books, their numbers rapidly declined due to agricultural practices, logging and infrastructure projects that have destroyed more than 90% of their habitat, compared to what they had available a century ago.

Protecting and restoring corridors

Victoria Aris Payne, from the World Resources Institute, where two authors in the Science article work (Nigel C. Sizer & Crystal L. Davis), explains that tigers are solitary by nature and require enormous areas of land (habitat) to survive.

One way of making sure their habitat range is vast enough is by protecting and restoring corridors – areas of land connecting large zones of habitat, which allow otherwise separated tiger populations to disperse and mingle.

A Sumatran Tiger. According to the World Wildlife Fund: “Sumatran tigers are the smallest surviving tiger subspecies and are distinguished by heavy black stripes on their orange coats. The last of Indonesia’s tigers—as few as 400 today—are holding on for survival in the remaining patches of forests on the island of Sumatra. Accelerating deforestation and rampant poaching mean this noble creature could end up like its extinct Javan and Balinese relatives.” (Image: World Wildlife Fund)

A Sumatran Tiger. According to the World Wildlife Fund: “Sumatran tigers are the smallest surviving tiger subspecies and are distinguished by heavy black stripes on their orange coats. The last of Indonesia’s tigers—as few as 400 today—are holding on for survival in the remaining patches of forests on the island of Sumatra. Accelerating deforestation and rampant poaching mean this noble creature could end up like its extinct Javan and Balinese relatives.” (Image: World Wildlife Fund)

Ms. Payne wrote:

“Habitat loss or gain in these relatively small areas have major impacts on the viability of tiger populations, as demonstrated in Nepal.”

The Khata corridor in Nepal’s Terai Arc Landscape – a region that encompasses three tiger conservation landscapes crucial for achieving the goal of doubling the wild tiger population by the year 2022, gained tree cover of approximately 2.7% of its area since 2002.

This gain was partly thanks to a community-managed forestry programme and the efforts of anti-poaching patrollers to protect the habitat and local fauna.

Tigers currently use this corridor to travel between India’s Katerniaghat Tiger Reserve and Nepal’s Bardia National Park. The use of this corridor has probably contributed to the remarkable increase from 18 to 50 tigers over the 2009-to-2013 period in Bardia.

An Indochinese Tiger. The World Wildlife Fund informed in 2010 that this subspecies’ population had declined by over 70% in just over sixty years. Six countries – Vietnam, Myanmar, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, China, Cambodia and Thailand – are now home to just 350 individuals. (Image: World Wildlife Fund)

An Indochinese Tiger. The World Wildlife Fund informed in 2010 that this subspecies’ population had declined by over 70% in just over sixty years. Six countries – Vietnam, Myanmar, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, China, Cambodia and Thailand – are now home to just 350 individuals. (Image: World Wildlife Fund)

The wild tiger population in the Terai Arc Landscape overall rose by 61% from 2009 to 2014.

The Basanta corridor, on the other hand, which is also in the Terai Arc Landscape in Nepal, lost some of its forest to land clearing and encroachment, and is not used by wild tigers any more to move to and from the northern forests.

The loss was small, just 0.7%. However, it happened in a bottleneck area, which effectively severed access between the northern and southern tiger populations in this area and significantly reduced the habitat range.

In order to secure future tiger populations, it is crucial that we prevent habitat loss.

The Bengal tiger is found mainly in India. There are also smaller populations in Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, China and Myanmar. It is the most numerous tiger subspecies, with about 2,500 left in the wild. The creation of India’s tiger reserves in the 1970s helped to stabilize numbers. (Image: World Wildlife Fund)

The Bengal tiger is found mainly in India. There are also smaller populations in Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, China and Myanmar. It is the most numerous tiger subspecies, with about 2,500 left in the wild. The creation of India’s tiger reserves in the 1970s helped to stabilize numbers. (Image: World Wildlife Fund)

Some bad news

Habitats where large-scale agriculture is driving deforestation are experiencing the greatest loss.

Most of the total forest loss (90%) in tiger habitats was concentrated in ten landscapes. Landscapes in Indonesia and Malaysia reported the highest percentage of loss, where conversion of forest to farmland is a major contributing factor.

According to World Resources Institute (WRI) research, globally we will need to produce 70% more food calories by the middle of this century than we produce today to feed a growing human population. The pressures to convert more forest land into farmland will be intense.

Ms. Payne wrote:

“Much of that demand will be met by commodities like palm oil. Strong forest management practices will be critical to balancing agricultural expansion so that it happens on already degraded lands and doesn’t cause damage to intact tiger habitat.

Regarding Tigers, the World Wildlife Fund writes: “This big cat is both admired and feared by people around the world. If forests are emptied of every last tiger, all that will remain are distant legends and zoo sightings.” (Image: World Wildlife Fund)

Regarding Tigers, the World Wildlife Fund writes: “This big cat is both admired and feared by people around the world. If forests are emptied of every last tiger, all that will remain are distant legends and zoo sightings.” (Image: World Wildlife Fund)

Preventing the extinction of Big Cats

If we do things properly, there is enough intact habitat to support a tiger population twice or even three times its current size in coming decades.

The lower-than-expected loss in Tiger Conservation Landscapes is a promising demonstration that progress is possible and is indeed happening. However, we absolutely cannot afford to lose any more.

The habitat that has vanished since 2001 could have supported 400 individual tigers – more than 10% of the current 3,500 individuals that exist today.

Experts forecast that globally we will invest $750 billion each year in infrastructure projects, including a superhighway going right through the Terai Arc Landscape.

Protecting the wild tiger and its populations will require a concerted effort to balance growing global demand with the right forest management practices.

Citation: “Tracking changes and preventing loss in critical tiger habitat,” Michael L. Anderson, David Olson, Matthew C. Hansen, Anup R. Joshi, Eric Dinerstein, Eric Wikramanayake Benjamin S. Jones, John Seidensticker, Susan Lumpkin, Nigel C. Sizer, Crystal L. Davis, Suzanne Palminteri and Nathan R. Hahn. Science Advances. 1 April 2016. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1501675.

Video – Tigers: Stop Wildlife Crime

This World Wildlife Fund video explains how the global wild tiger population has plummeted over the past 100 years from about 100,000 individuals to barely more the 3,200.