A badger was observed by a team of biologists from the University of Utah burying a whole cow on its own. The amazed scientists said no similar event – burying an entire cow carcass by itself – had ever been documented before.

We have long known that badgers and their relatives cache their food stores. This latest finding, however, suggests that badgers appear to have no limit on the size of animal that they cache.

In an article published in Western North American Naturalist, Vol. 77 : No. 1 , Article 13 – ‘Subterranean caching of domestic cow (Bos taurus) carcasses by American badgers (Taxidea taxus) in the Great Basin Desert, Utah’ – Ethan H. Frehner, Evan R. Buechley, Tara Christensen and Çağan H. Şekercioğlu, all from the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said that badgers may play an important role in sequestering large carcasses, which might benefit livestock farmers in the West.

This is the first time a badger has been observed burying a creature larger than itself. (Image: unews.utah.edu)

This is the first time a badger has been observed burying a creature larger than itself. (Image: unews.utah.edu)

First author, Ethan Frehner, Associate Instructor at the University’s Biology Department, said:

“We know a lot about badgers morphologically and genetically, but behaviorally there’s a lot of blank spaces that need to be filled. This is a substantial behavior that wasn’t at all known about.”

Badger not researchers original target

Frehner and colleagues had not originally planned to study the badger. In January 2016, Evan R. Buechley, a Graduate Teaching Assistant (Biology) who studies vultures and other avian scavengers, set out seven calf carcasses in the Grassy Mountains in Utah’s West Desert.

Each carcass was held in place with a stake and equipped with a camera trap to record what scavengers would feed on which carcasses. Buechley wanted to learn more about scavenger ecology in the Great Basin during the winter months.

One week after placing the carcasses, Buechley went out to check them and noticed that there were only six – one was missing.

Buechley said:

“When I first got there I was bummed because it’s hard to get these carcasses, to haul them out and set them up. I thought ‘Oh, well we’ve lost one after a week.’”

Badgers place their food in an environment that makes them last longer – like we use a fridge. (Image: unews.utah.edu)

Badgers place their food in an environment that makes them last longer – like we use a fridge. (Image: unews.utah.edu)

He wondered whether perhaps a mountain lion or coyote may have dragged the carcass away. After searching around the area he did not find anything. When he returned to the ground where he had placed the carcass, he noticed that it had been disturbed.

Buechley added:

“Right on the spot I downloaded the photos. We didn’t go out to study badgers specifically, but the badger declared itself to us.”

A very happy badger

Badgers are shy animals. We do not know that much about their behaviors because they spend most of their lives underground, and come out into the open mainly at nighttime.

Regarding badgers, Frehner said:

“They’re an enigmatic species. A substantial amount of their lifetime is spent either underground or a lot of nocturnal behavior, so it’s hard to directly observe that.”

Thanks to camera traps, which have only been used by researchers relatively recently, it has become possible to observe natural badger behavior more extensively.

The well-fed badger sitting contently atop the burrow (the calf carcass is buried underneath). (Image: unews.utah.edu)

The well-fed badger sitting contently atop the burrow (the calf carcass is buried underneath). (Image: unews.utah.edu)

Buechley could see in the photographs taken by the camera that the badger had dug around and beneath the carcass, which eventually disappeared into the cavity created by the animal’s excavation.

Frehner said:

“Watching badgers undertake this massive excavation around and underneath is impressive. It’s a lot of excavation engineering they put into accomplishing this.”

Badger buried carcass in 5 days

The photographs showed that the badger managed to completely bury the 50-pound carcass within five days of digging around and beneath it. It then spent about 14 days in his underground burrow before leaving.

Over the next few weeks, until early March, the badger returned several times to the burrow.

The authors said that badgers cache food for two reasons: 1. To isolate it from other scavengers. 2. To keep it somewhere where it will last longer.

Buechley explained that what badgers do is similar to what we do when we store our food in a fridge. Biologists had previously seen badgers caching rabbits and rodents, but never an animal bigger then itself.

Co-author Tara Christensen assembled a time-lapse video of the carcass burial. It shows the badger sitting happily on top of the burrow.

Regarding the badger in the photographs, Buechley said:

“Not to anthropomorphize too much, but he looks like a really really happy badger, rolling in the dirt and living the high life.”

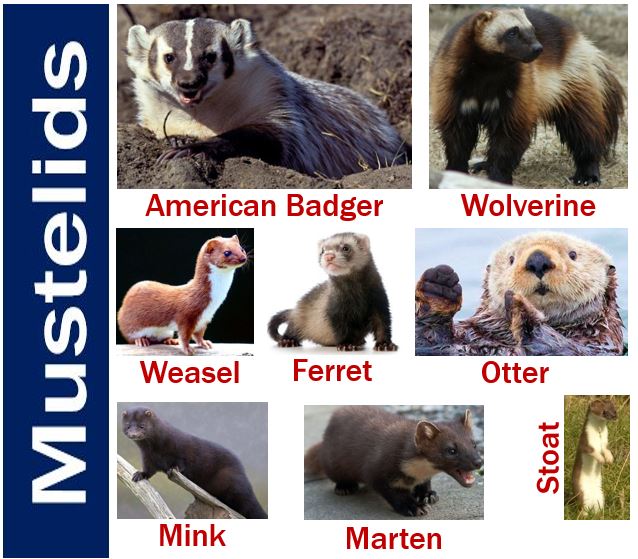

Mustelids (Mustelidae) are a family of carnivorous mammals, including the badger, otter, weasel, mink, stoat, wolverine, ferret, and marten. They range in size from the ‘least weasel’, which is not much bigger than a mouse, to sea otters that can weigh in excess of 99 pounds (45 kg).

Mustelids (Mustelidae) are a family of carnivorous mammals, including the badger, otter, weasel, mink, stoat, wolverine, ferret, and marten. They range in size from the ‘least weasel’, which is not much bigger than a mouse, to sea otters that can weigh in excess of 99 pounds (45 kg).

Ecological role of badgers

In another site in the same study, a different badger also tried to bury a calf carcass. This suggests that the behavior seen in the time-lapse video is widespread for badgers.

In an Abstract preceding the main article, the authors wrote:

“One carcass was partially buried and the other was entirely buried. Both badgers constructed dens alongside their cache, where they slept, fed, and spent up to 11 days continuously underground. They abandoned the sites 41 and 52 days after initial discovery.”

“While badgers are known to scavenge and to cache small food items underground, this is the first evidence of an American badger caching an animal carcass larger than itself.”

We do not know whether mustelids – badger relatives – can also cache such big animals. Weasels, otters, ferrets, badgers, martens, minks, wolverines and stoats are mustelids.

Martens, wolverines and weasels are not as specialized for digging as badgers are. The authors said there is one account of a mustelid caching a black bear carcass under bracken and branches.

Large-animal caching may have an important impact in the sparse and harsh ecosystem of the Great Basin, said Buechley.

Regarding the Great Basin, Buechley said:

“There’s not a lot of resources out there. A large dead ungulate can provide a ton of resources. So far on the carcasses we’ve put out, we’ve had turkey vultures, golden eagles, many ravens, bobcats, kit fox and coyote, so there’s a lot of animals that could be using this resource, and the badger just monopolizes it.”

Ranchers generally see the badger as a pest. The animal eats chickens and digs burrows through range-land. However, if a badger is capable of burying a calf, they may bury other carcasses before any disease have a chance to incubate and infect farmers’ livestock.

Frehner said:

“It’s not beneficial to have rotting carcasses out among your other cattle because of disease vectors. Keeping large predators away is a big deal for a lot of ranchers.”

Christensen added:

“You could argue that if the carcasses are being buried, they’re not going to be attracting large predators.”

Both Christensen and Frehner took part in this study as undergraduates, which gave them valuable insight into the research process.

Christensen said:

“Doing research and getting involved in a lab is a great way to see how science is done. I’ve learned a lot in the last few months about data analysis and using these things to find real results.”

As far as Frehner was concerned:

“Writing the paper has been a substantial learning experience for me that I don’t think I would have gotten any other way.”

Regarding the whole study and their findings, Buechley said:

“This adds more questions than it answers. The nutrients in a carcass can be very important for many different organisms in an ecosystem. So if badgers are monopolizing them and they have the ability to bury perhaps any mammal carcass in North America and they’re present across much of the continent, the potential ecological implications are profound.”

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Evan Buechley, a doctoral candidate.

Video – Badger burying a cow

In this University of Utah time-lapse video, you can see the badger burying the calf carcass over a period of five days, and finally sitting atop the burrow.

The badger managed to completely bury an animal three or four times its weight.