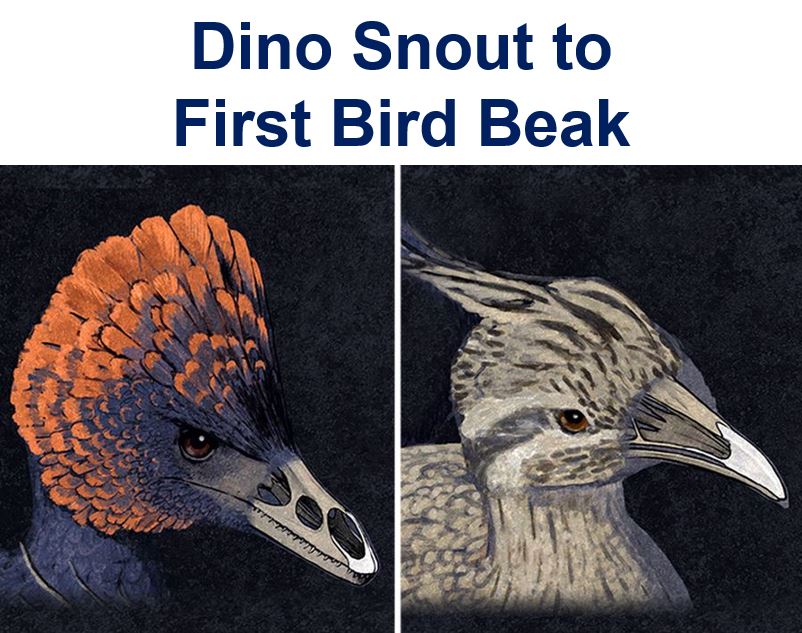

Scientists have managed to replicate the molecular process that led to the first bird beaks from dinosaur snouts by using the fossil record as a guide. This is the first successful reversion of a bird’s skull features.

The research team, led by Harvard developmental biologist Arhat Abzhanov and Yale paleontologist and developmental biologist Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar, replicated ancestral molecular development to transform chicken embryos in the lab into specimens with a dino-type snout and a palate configuration similar to that of the Archaeopteryx and Velociraptor, two types of small dinosaurs.

The scientists, who published details of their study in the academic journal Evolution (citation below), jokingly requested readers not to call their specimens ‘dino-chickens’.

Scientists retraced the bird’s beak to its dinosaur origins, in the lab. (Image: Yale)

Lead author, Prof. Bhullar said:

“Our goal here was to understand the molecular underpinnings of an important evolutionary transition, not to create a ‘dino-chicken’ simply for the sake of it.”

Scientists, authors and lay people have long been interested in finding a mechanism to recreate elements of dinosaur physiology. It has been featured in everything from the upcoming film ‘Jurassic World’ to molecular biologist Jack Horner’s 2009 book ‘How to Build a Dinosaur’.

The researchers, in this case, were interested in the importance of the beak to avian anatomy.

Bird’s beak crucial for avian feeding

Prof. Bhullar explained:

“The beak is a crucial part of the avian feeding apparatus, and is the component of the avian skeleton that has perhaps diversified most extensively and most radically — consider flamingos, parrots, hawks, pelicans, and hummingbirds, among others.”

“Yet little work has been done on what exactly a beak is, anatomically, and how it got that way either evolutionarily or developmentally.”

In this new study, the authors detail a new approach to finding the molecular mechanism involved in creating the beak’s skeleton.

They started off by doing quantitative analysis of the anatomy of related fossils and animals that exist today to generate a hypothesis regarding the transition. Then they searched for possible changes in gene expression that correlated with the transition.

Prof. Bhullar and colleagues looked at gene expression in the embryos of turtles, lizards, alligators and emus.

Birds are descended from dinosaurs.

They found that both major living lineages of birds – the common neognaths (virtually all flying birds) and less common paleognaths (flightless birds) – differ from the major lineages of non-bird reptiles – lizards, turtles and crocodiles – and from mammals in “having a unique, median gene expression zone of two different facial development genes early in embryonic development.”

Scientists had previously observed this median gene expression only in chickens.

The researchers were able to induce the ancestral molecular activity and ancestral anatomy by using small-molecule inhibitors to block the activity of the proteins produced by the bird-specific, median signaling zone in chicken embryos.

Scientists reverted bird’s beak

Not only did the structure of the beak revert, but the procedure also caused the palatine bone on the roof of the bird’s mouth to go back to its ancestral state.

Prof. Bhullar said:

“This was unexpected and demonstrates the way in which a single, simple developmental mechanism can have wide-ranging and unexpected effects.”

The team then moved from the alligator nests at the Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge in southern Louisiana to an emu farm in Massachusetts. They extracted DNA from several species in order to clone fragments of genetic material in their quest to find specific gene expression.

According to Prof. Bhullar, the study has several implications. For example, if a single molecular mechanism caused this transformation, there should be a corresponding, associated transformation in the fossil record.

Prof. Bhullar said:

“This is borne out by the fact that Hesperornis – discovered by Othniel Charles Marsh of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History – which is a near relative of modern birds that still retains teeth and the most primitive stem avian with a modernized beak in the form of fused, elongate premaxillae, also possesses a modern bird palatine bone.”

Premaxillae, the small bones located at the tip of the upper jaw of most animals, are fused together and enlarged to form the beak of birds.

Prof. Bhullar pointed out that the approach they used could be utilized to study the underlying developmental mechanisms of several evolutionary transformations.

Citation: “A molecular mechanism for the origin of a key evolutionary innovation, the bird beak and palate, revealed by an integrative approach to major transitions in vertebrate history,” Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar, Zachary S. Morris, Elizabeth M. Sefton, Atalay Tok, Msayoshi Tokita, Bumjin Namkoong, Jasmin Camacho, David A. Burnham and Arhat Abzhanov. Evolution. DOI: 10.1111/evo.12684.