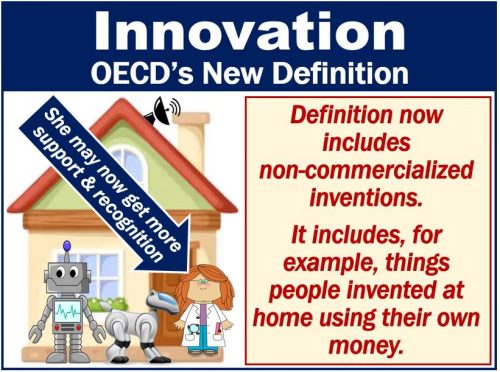

Non-commercial innovators will get more credit under a new definition of innovation. This could mean more backing for household innovators and subsequently more innovation. The OECD has just changed the definition of the term.

OECD stands for the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. It is a unique forum where the governments of thirty-five countries work with each other. Every OECD member is a democracy with a market economy. The OECD aims to promote prosperity, sustainable development, and economic growth.

The product keeps people with diabetes safe, and the community offers plans to create it for free online.

OECD’s definition of innovation

However, until now, under the OECD’s definition of the term, it had not counted such clear examples as innovation. All this changed on October 24th.

The OECD’s new edition of the Oslo Manual has revised its definition of innovation. The Oslo Manual is a guidebook for gathering and using data on industrial innovation. Most countries use it.

According to the Oslo Manual, the new product no longer needs to be commercialized first to be counted.

In his book ‘Free Innovation’ (citation below), MIT Sloan Professor of Technological Innovation, Eric von Hippel argues that ‘free’ innovations do not get enough support. Free or household innovations are those that people develop on their own time and with their own money.

They do not get enough support because public policymakers are not recognizing their creations for what they are. This is despite a sizable proportion of new ideas coming from people developing things in their own time with their own money.

OECD’s previous definition

The OECD had previously defined innovations as products that had entered the market. In other words, products that were for sale and that people were buying.

Under the old definition, tens of millions of people spending billions of dollars developing and modifying products each year never got credit for their innovations. They never got credit because ninety percent of them gave their innovations away.

Take, for example, mountain bikes. Household innovators designed and created the first mountain bikes. However, they never received any credit, said Prof. von Hippel.

Prof. von Hippel said:

“Basically, the end result is a distorted system where businesses get a lot of credit for a lot of innovations they didn’t do. This, in turn, biases public policy toward the needs of companies and their intellectual property rights.”

“Now, finally, with a better OECD definition and better data we’ll be in a position to allocate innovations to the people who actually develop them.”

“That in turn will make household sector innovation visible to government policymakers, and induce people to make a more level playing field where both consumer innovators and producer innovators are acknowledged and supported.”

OECD’s revised definition of innovation

The OECD’s new definition of innovation now reads as follows:

“An innovation is a new or improved product or process, or combination thereof, that differs significantly from the unit’s previous products or processes and that has been made available to potential users (product) or brought into use by the unit (process).”

In this definition, the word ‘unit‘ is a generic term that describes the actor responsible for innovations. The ‘unit’ could be any institutional unit in any sector, as well as households and their individual members.

Tinkering leads to new inventions

Prof. von Hippel and colleagues researched consumer innovations across ten countries. They found that the phenomenon generated a research and development capital stock of approximately $250 billion just in the USA.

Consumers have been creating new products in virtually all areas of the consumer market.

Prof. von Hippel said:

“If there is nothing out there, consumers will build it for themselves. Ninety percent of these people just give [innovations] away for free, and the other 10 percent is where a lot of entrepreneurship comes from. That means 90 percent of innovation occurring in the household sector hasn’t been counted.”

“If the household sector is developing many generally valuable innovations, this increases social welfare just as producer innovation does, and society ought to level the playing field and support both household sector innovation and producer innovation.”

Citation

von Hippel, Eric, Free Innovation (November 8, 2016). E von Hippel, 2017. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2866571