Giffen Goods are products whose demand increases when prices rise, thus reversing the typical law of prices and demand.

In most cases, when prices rise, demand for that product declines – the opposite occurs with Giffen goods.

In the vast majority of cases, Giffen goods are very basic products – inferior products – which low-income households rely on.

Poor people have a very limited choice of food. For example, in Victorian Britain bread was the basic foodstuff for those at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder.

If Victorian bread prices increased, poor households could not switch to any alternatives. Meat was very expensive, so people ended up purchasing more bread – and less meat, or even did away with meat altogether – because bread was the only thing they could afford.

A rise in the price of bread makes such a large drain on poor people’s resources and raises so much the marginal utility of money for them, that they must cancel their consumption of meat and other more expensive foods, and consume even more bread because even though it is now more expensive, it is still the cheapest food around; the only one they can afford.

Giffen goods named after Robert Giffen

Giffen goods are named after Sir Robert Giffen (1837-1910), a Scottish statistician and economist, to whom Alfred Marshall (1842-1924), one of the most influential economists of his time, attributed this idea in his book Principles of Economics.

Sir Robert had first proposed the paradox – of demand growing after a basic food rose in price – from his observations of the buying habits of the Victorian era poor.

In his book Principles of Economics, Marshall Wrote:

“As Mr. Giffen has pointed out, a rise in the price of bread makes so large a drain on the resources of the poorer laboring families and raises the marginal utility of money to them so much that they are forced to curtail their consumption of meat and the more expensive farinaceous foods: and, bread being still the cheapest food which they can get and will take, they consume more, and not less of it.”

* The singular of ‘Giffen goods’ is a ‘Giffen good’.

Do Giffen goods exist?

There is very limited evidence demonstrating the existence of Giffen goods. Many people say that they are a myth.

During the Irish Potato Famine, the price of potatoes rose. People at the time were so poor that they began substituting potatoes, a dietary staple, for meat and other non-basic luxuries. The Irish ended up consuming more potatoes as a result – so the legend goes.

However, the problem with the Potato Famine example was that there was a supply shortage, making it extremely unlikely that people were able to consume more potatoes. If something is in short supply, how can its consumption increase?

The Economist quotes two economists – Robert Jensen and Nolan Miller – who believe there is a modern example of Giffen goods. Poor people in China consume more rice – their staple – when prices rise. Jensen and Miller say the idea is the same as supposedly occurred during the Irish famine.

Humans need a certain number of calories to stay alive, let’s say 1,600 each day. That can be obtained by eating rice and maybe some vegetables alone, or consuming rice, vegetables, and small quantities of meat.

However, meat is expensive. For these poor people, if the price of rice goes up, they no longer have any money to buy decent quantities of meat. Whatever money they have, they use to purchase more rice in their attempt to reach the required 1,600 calories per day. Rice in this situation is a Giffen good.

Giffen Goods are named after Sir Robert Giffen, a Scottish economist and statistician. (Image: wikieducator.org)

Giffen Goods are named after Sir Robert Giffen, a Scottish economist and statistician. (Image: wikieducator.org)

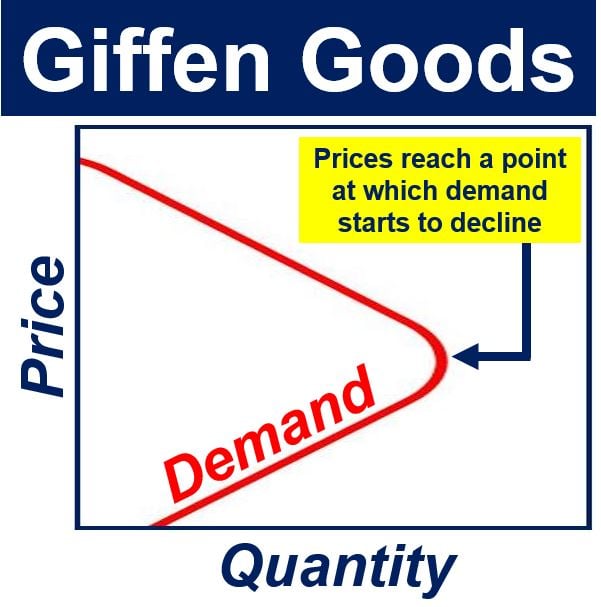

Prices of Giffen goods have a maximum

Demand for a Giffen good cannot keep rising in parallel with its price rise forever. Eventually, the consumer will run out of money. Giffen goods must be inferior goods, which implies that those who buy them have little money to start with.

As some point, the increasing price of the Giffen good takes over the purchaser’s entire budget, and a price rise will actually reduce the amount of the good the consumer is able to purchase.

In other words, at high enough prices, there will eventually be the traditional decline in demand, even as far as Griffin goods are concerned.

Imagine you are given a budget of $60 to purchase potatoes and chicken breast to buy meals for ten days. Potatoes start off at $1 each and chicken breast at $20 per box.

With the original prices and budget, you may choose to purchase two chicken breast boxes, at $40, and 20 potatoes for $20 over the ten-day period to use up your entire budget. This is fine, because you will have on average two potatoes per day and two boxes of chicken breast over the period.

However, the price of potatoes suddenly goes up to $2 each. You could still purchase two chicken boxes – if you did so, you would only be able to buy ten potatoes. This might not be enough to satisfy your daily calorie requirement. However, if you purchase less chicken, say just one box every ten days, you can still have your 20 potatoes.

The unusual demand pattern for Giffen goods highlights the complex nature of consumer behavior, which often defies conventional economic models and assumptions about rationality.

Lets say the price of potatoes goes up again, to $2.50, which means that for $40 dollars you will only be able to purchase sixteen potatoes. This will not cover your daily calorie requirement. However, if you give up chicken completely and just buy potatoes, you will not starve. For $60 (your budget) you can buy 24 potatoes.

In this example, your demand for potatoes increased from 20 to 24 for the ten-day period after the price rose from $1 to $2.50 each.

If the price of each potato now rises again, to $4 each, all you can afford are 15 potatoes every ten days (no chicken at all). The potato is no longer a Giffen good – your demand is declining. You only have so much money.

Demand for Veblen goods also increases when their prices go up – but for a very different reason. Veblen goods are ultra-luxury items – superior goods. People buy them because they are expensive.

Demand for ‘Normal Goods’ goes up when incomes rise, but by slightly less than the increase in incomes. People at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder purchase lots of supermarket brand or generic goods. When their incomes increase, they move onto the more expensive brand products – normal goods.

Types of goods

In business/economics/financial English, there are many different terms that describe “goods.” Let’s have a look at some of them:

Items and products used within households.

Example: “She made a list of household goods they needed, including towels and a dustbin.”

Products that are purchased for consumption by the average consumer.

Example: “The store offers a variety of consumer goods ranging from food to electronics.”

-

Normal Goods

Goods for which demand increases when consumer income rises.

Example: “As the economy improved, more people started buying organic produce, a typical example of normal goods.”

-

Veblen Goods

High-status items for which the demand increases as the price increases due to their exclusivity and status symbol.

Example: “Designer handbags are often considered Veblen goods; the more expensive they are, the more sought after.”

Electronic consumer items related to audio-visual, entertainment, and home computing.

Example: “He decided to upgrade his home theater, so he looked into the latest brown goods on the market.”

Large home appliances which were traditionally available only in white, such as refrigerators and washing machines.

Example: “The kitchen was equipped with the latest white goods, including an energy-efficient dishwasher.”

Goods that are used in producing other goods, rather than being bought by consumers.

Example: “The company invested in new capital goods to increase its production capacity.”

Items that are often bought spontaneously without planning, due to a sudden desire.

Example: “Candy bars placed near the checkout counter are classic impulse goods.”

Products that are non-excludable and non-rivalrous, meaning they can be used by everyone and one person’s use does not diminish another’s.

Example: “The local government focused on improving public goods like parks and roads.”

Products or services that can be used in place of each other.

Example: “With the rising price of coffee, some consumers may turn to tea as a substitute good.”

Video – What are Giffen Goods?

This video, from our YouTube partner channel – Marketing Business Network, explains what ‘Giffen Goods’ means using simple and easy-to-understand language and examples.