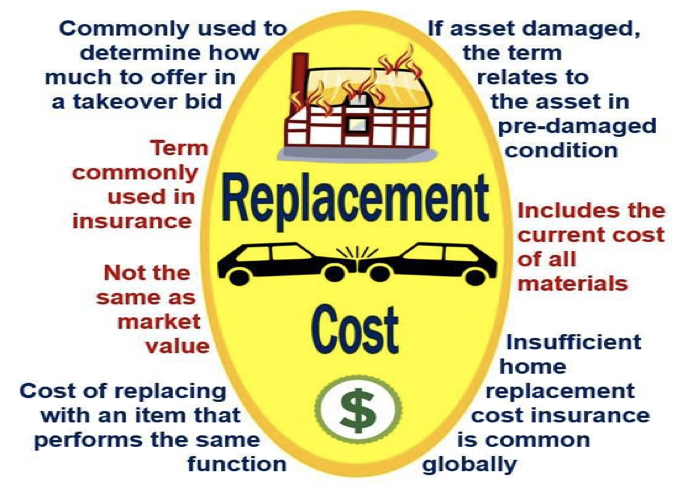

Replacement cost – replacement cost value or replacement value – refers to how much it would cost an individual, company or any entity to replace a current asset at today’s market prices with the same or similar asset. If the replacement cost being calculated is of a damaged asset, then that cost relates to the asset in pre-damaged condition.

Assets’ replacement costs may not be the same as their market value, because the asset that would be needed to replace something might have a different cost. The replacement asset does not have to be an identical item – it only needs to perform the same function as the one in question.

Companies’ accountants use depreciation to expense the cost of each asset over its useful life.

If an asset is damaged, destroyed or lost, it is important to know how much it would cost to replace it. The same applies for an item your company has sold.

If an asset is damaged, destroyed or lost, it is important to know how much it would cost to replace it. The same applies for an item your company has sold.

Replacement cost vs. market value

The replacement costs of items refers to how much the business will spend to restock them after they are sold.

As a lot of business items are sold at wholesale prices in bulk, the cost of replacing them may fluctuate over time, depending on any deals the company can negotiate, the supplier’s pricing, and the size of its orders.

Market value refers to an item’s retail price. This also fluctuates because of special deals that are offered to customers.

So, while replacement cost is used to determine how much a company will spend to restock an item, or if it has been rendered unsalable while in the warehouse, market value determines whether the inventory on hand is enough to maintain the sales volume that the management expects over the next sales period.

A company’s inventory’s market value is a reassuring number – at least on paper – because it shows that there is an immediate profit over its replacement cost. However, that firm cannot spend that amount of money until the items have been sold.

The market value of an asset is rarely the same as its replacement cost.

The market value of an asset is rarely the same as its replacement cost.

If a business were forced to sell its entire inventory in one go, it would probably only be able to sell it at wholesale cost. The message here is to use market value just for planning ahead, rather than relying on it as a cash flow value.

In an article published in the Journal of Property Investment & Finance in 2009 – ‘Replacement Cost and Market Value’ – Peter Wyatt, from the School of Real Estate and Planning, Reading University, UK, wrote:

“Defining replacement cost as a method of estimating market value rather than a separate basis of value blurs the distinction between cost and value. This paper argues that market value assumptions do not hold in the case of the replacement cost method.”

According to Accounting Coach, replacement cost is:

“The amount needed to replace an asset such as inventory, equipment, buildings, etc. If an asset’s replacement cost is greater than the asset’s carrying amount, the cost principle prohibits the use of the replacement costs in the financial statements distributed by a company.”

“However, economists and decision makers believe that replacement cost is more relevant than the historical cost.”

Replacement cost – insurance

The term is commonly used in insurance policies to cover damage to a commercial enterprise’s assets. The definition of the asset in question is crucial, given that the insurance company will be liable to pay the insured for its replacement cost if it is lost, stolen, destroyed or damaged.

When insuring property, insurance policies typically have a contractual stipulation that the lost asset has to be replaced or repaired before the replacement cost can be paid. The aim here is to prevent overinsurance, which contributes to illegal insurance-related activities, such as arson.

Up until the middle of the last century, replacement cost policies did not exist – their availability was restricted due to concern about overinsurance.

If the insurance company honestly determines replacement costs, it is a win-win for both the insurer and insured.

However, when the insurance company’s cost determination is greater than the actual cost of replacement, the insured (the owner of the asset) is probably paying too much for insurance.

In fact, overvaluing a customer’s asset so that higher premiums are paid may constitute consumer fraud.

Insurance companies buy replacement cost estimate lists. Major estimation companies include Verisk Analytics PropertyProfile, Marshall Swift-Boeckh (subsidiary of CoreLogic), E2Value, and Bluebook International. Home Smart Report and AccuCoverage have estimates for consumer goods.

Your home – replacement cost

If you have insufficient insurance to cover the cost of replacing your home and it is destroyed in a fire, earthquake, hurricane or other catastrophic event, you will probably have to pay considerable uninsured costs out of your own pocket.

Underinsurance of personal property – homes – is common across the world. A survey carried out in 2013 found that approximately sixty-percent of US homes had replacement cost estimates that were 17% below the actual cost of replacing the property.

Sometimes, estimates for replacement costs may be too low due to ‘demand surge’ following a catastrophe.

Replacement cost in mergers and acquisitions

When trying to predict how much it would cost to duplicate another business, it is common to use the replacement costs of assets.

During a takeover attempt, the predatory company will use this replacement-cost concept to determine one of several price-per-share offers to the stockholders of the target company.

By accurately estimating replacement costs, the predatory company – the one that wants to acquire the other – is less likely to offer too little, and lose the bid, or offer to much.

Video – Difference between replacement cost and actual cash value

This Insurance A Ref video explains the meaning of insurance cost using simple language and easy-to-understand terms.

The speaker begins by comparing replacement costs with actual cash values, and then gives us an example of a homeowner’s insurance claim, describing the difference between the two terms.