The wealth effect is a psychological phenomenon in which an increase in the value of bonds, property, stocks and other assets makes people feel ‘richer’, so they spend more; there is a rise in aggregate demand.

Even though no extra liquid cash is created, the wealth effect encourages people to save less and spend more – this boosts GDP (gross domestic product) growth.

If interest rates go up, future income from equities and other such assets must be discounted at a higher rate than before – the owners of such assets feel poorer and tend to spend less.

This is the negative wealth effect – when it works the other way round.

Put simply, as our perception of personal wealth grows – as we feel richer – we consume more. So, when the value of our shares, property and other assets rise we spend more and save less, and when they decline we save more and spend less. This is all due to the ‘wealth effect’.

Consumers spend more when one of two things occurs:

– When we actually are richer – for example, when we receive a pay rise.

– When we perceive ourselves to be richer – for example, when the assessed value of our home goes up, or a stock that we own appreciates in value.

This theory refers to spending among both individual consumers and businesses. Companies hire more and spend more on capital expenses as they feel more secure.

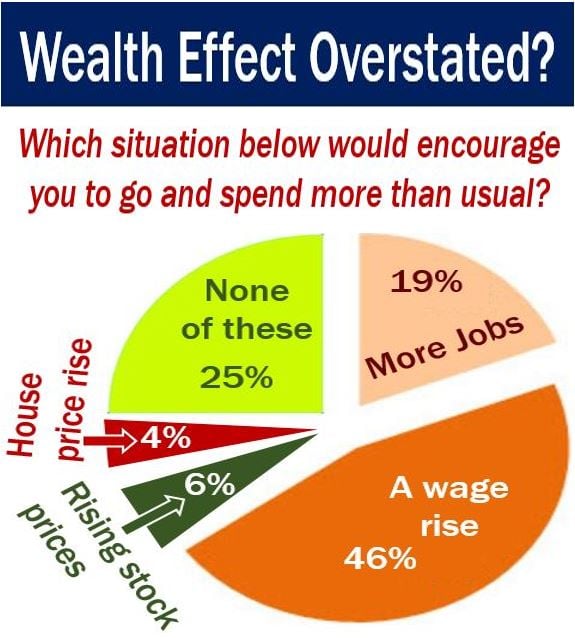

In a 2013 Reuters article, Pedro da Costa argues that real wages are what drive US consumer spending, and not the wealth effect. In the image above, the two items that would boost the wealth effect are ‘House price rise’ and ‘Rising stock prices’ – combined, they only totaled 10% in a survey of American consumers, compared to ‘A wage rise’, which registered 46%. (Image: adapted from blogs.reuters)

In a 2013 Reuters article, Pedro da Costa argues that real wages are what drive US consumer spending, and not the wealth effect. In the image above, the two items that would boost the wealth effect are ‘House price rise’ and ‘Rising stock prices’ – combined, they only totaled 10% in a survey of American consumers, compared to ‘A wage rise’, which registered 46%. (Image: adapted from blogs.reuters)

Wealth effect and tax hikes

There have been times in history when an increase in income tax did not trigger a decline in aggregate demand. In most cases, economists put it down to the wealth effect caused by a strong stock market.

In 1968, income tax in the United States rose by ten percent, but there was no subsequent slowdown in consumer spending.

Economists were initially unable to explain why, but later attributed the sustained aggregate demand to the wealth effect.

While the income tax hike reduced people’s disposable income, the stock market had been rising, which increased people’s wealth and perceived wealth significantly. Undaunted by the sudden loss of disposable income, people continued spending at the same rate, because of the wealth effect.

Wealth effect in a bull or bear market

A bull market is one in which stock prices are rising in value. During a bull market, the wealth effect is known to boost GDP growth.

Most people’s investment portfolios contain a major proportion of stocks and shares. Big gains in stock prices can make people feel more optimistic and secure about their personal wealth and their spending – they spend more.

However, during a bear market, when stock prices are declining, it works the other way round. During bear markets people feel less secure about their wealth, so they spend less, which undermines GDP growth.

Demand for inferior goods declines as people become wealthier or feel richer. Examples of inferior goods are supermarket brands or hamburgers at fast-food restaurants.

When people are under the ‘spell’ of the wealth effect, they tend to go to fast-food restaurants less often, but visit more expensive restaurants more frequently.