Fracking is a controversial subject, but may become a much more popular prospect if up to £10,000 in cash is paid to each household that is affected. The money will come from the Shale Wealth Fund that oil & gas exploration companies contribute to. The household does not necessarily have to be affected – it just needs to be located near fracking well sites.

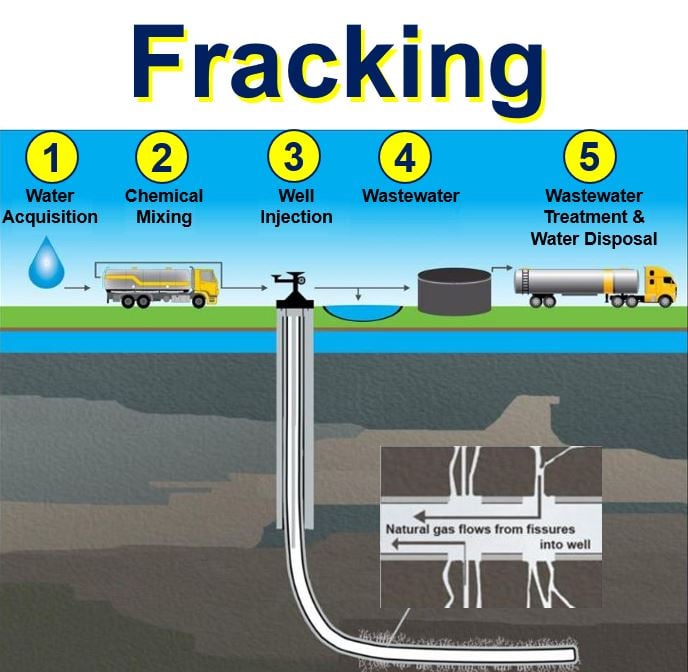

Fracking refers to the extraction of natural gas from under the ground through hydraulic fracturing – often oil is also extracted during the process.

The government has suggested that the Shale Wealth Fund – up to ten percent of tax proceeds from fracking – which was unveiled in 2014 as a way of compensating local communities, should be given directly to individual households rather than local trusts and councils.

Fracking has been around for over six decades. Large-scale natural gas production from shale started at the turn of this century, when shale gas production became a commercial reality in the Barnett Shale in north-central Texas. (Image: adapted from www.epa.gov)

Fracking has been around for over six decades. Large-scale natural gas production from shale started at the turn of this century, when shale gas production became a commercial reality in the Barnett Shale in north-central Texas. (Image: adapted from www.epa.gov)

Prime Minister Theresa May says she is considering paying the money directly to homeowners. A consultation, which will be outlined on 8th August, will put forward this option as one of a number of possibilities.

Each community that has wells sited could benefit to the tune of up to £10 million. The Government does not have to make an either-or decision, it can opt for a combination of direct cash to households plus money for councils and local trusts.

The Shale Wealth Fund

The £1 billion Shale Wealth Fund, which was unveiled by the former Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne in November Autumn Statement, will set aside about ten percent of fracking tax proceeds to benefit the communities where wells are sited.

In his Autumn Statement, Mr. Osborne said:

“We are supporting the creation of the shale gas industry by ensuring that communities benefit from a Shale Wealth Fund (SWF), which could be worth of up to £1 billion ($1.32 billion).”

If you lived in a community – with 100 homes – where wells were sighted, would you prefer to receive £10,000 directly or have your Council receive £1 million? In the second option you would get nothing.

If you lived in a community – with 100 homes – where wells were sighted, would you prefer to receive £10,000 directly or have your Council receive £1 million? In the second option you would get nothing.

The fund was designed to win over residents and local councils in areas affected by shale exploration (fracking exploration). It followed the Department of Energy and Climate Change’s previous announcement that the Government’s energy policy would see natural gas play a major role in the country’s future power generation plans.

With Britain’s coal-fired power stations probably closing down by 2025, there is currently an urgent push to add more natural gas into the country’s future energy mix.

The Prime Minister said ahead of Monday’s consultation that she would like to make sure that individual residents benefitted personally from economic decisions made by the government.

Mrs. May said:

“[The Government want to help] ordinary families for whom life is harder than many people in politics realise. This announcement is an example of putting those principles into action.”

“It’s about making sure people personally benefit from economic decisions that are taken – not just councils – and putting them back in control over their lives.”

Mrs. May said she would like to see the same approach applied to all future projects.

Although opposition to fracking appears to be widespread and strong, evidence suggests that the majority of Britons believe the benefits it offers are worth it. (Image: keeptapwatersafe.org)

Although opposition to fracking appears to be widespread and strong, evidence suggests that the majority of Britons believe the benefits it offers are worth it. (Image: keeptapwatersafe.org)

Economic compensation or a bribe?

While probably going a long way to countering resident resistance to fracking, giving money directly to households at the cost of projects that could benefit the community is likely to be characterised by critics is a giant bribe.

What is better for the local community as a whole, setting up or improving important projects such as skills training or infrastructure, or giving each household a load of cash?

According to a British Geological Survey (BGS) study across the north of England, there are approximately 1,300 trillion cubic feet of natural gas under the ground. This would satisfy the UK’s gas consumption needs at current levels for more than five centuries.

The Government seeks comments on its Shale Wealth Fund proposal and will publish its response by the end of this year.

Many people argue that we should be investing more on renewable energy sources that do not pollute, rather than finding new ways of using fossil fuels more extensively. (Image: guim.co.uk)

Many people argue that we should be investing more on renewable energy sources that do not pollute, rather than finding new ways of using fossil fuels more extensively. (Image: guim.co.uk)

What is fracking?

Fracking is short for hydraulic fracturing, a kind of drilling that has been around for more than sixty-five years.

A hole is drilled a mile or more below the land’s surface before gradually turning horizontal and continuing for a several thousand feet more.

If a viable well is found within the underground rock, it is drilled, cased and cemented. Small perforations are made in the horizontal part of the well pipe, which pumps out a mixture of water, sand and additives at high pressure to create tiny fractures in the rock. These fractures are held open by grains of sand.

Put simply, ‘fracking fluid’ is pumped into the wellbore at high pressure, this creates cracks in the deep-rock formations through which natural gas and brine flow more freely – if oil is present it will also flow.

When the hydraulic pressure is removed, tiny grains of sand or aluminium oxide hold the fractures open.

Opposition to fracking

In many countries fracking is highly controversial. Supporters say it gives us access to huge quantities of hydrocarbons, creates jobs and is good for the economy. Hydrocarbons are compounds made of just carbon and hydrogen. Crude oil and coal, for example, contain hydrocarbons.

Opponents argue that rather than spending billions on extracting fossil fuels, which exacerbate our current and future global warming problems, we should be pursuing environmentally friendly ways of producing energy, including solar, wind and tidal energy.

Two years ago, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) in the United States identified a link between hydraulic fracturing and earthquakes. Following this discovery, ODNR Director James Zehringer introduced new, stricter permit conditions for drilling near to areas with a history of seismic activity or faults.

In March 2014, there were two earth tremors in Poland Township, 70 miles southeast of Cleveland. Fracking and drilling activities close to the site of the two earthquakes were suspended.

In 2015, scientists from Aberdeen University’s School of Geosciences and colleagues in Australia announced that UK shale has large quantities of poisonous selenium.

Selenium exists in the human body in tiny amounts. However, it is toxic when levels are high. Levels of selenium in rock samples from the Bowland Shale, a geological formation that is rich in shale gas in the north of England, were found to be ‘very high’.

Excessively high levels of selenium can cause selenosis, which has the following symptoms: fatigue, irritability, sloughing of nails, neurological damage, gastrointestinal disorders, and halitosis (bad breath). In extreme cases people can develop pulmonary edema and/or cirrhosis of the liver.

Fracking in the United States

According to whatisfracking.com:

“Safe hydraulic fracturing is the biggest single reason America is having an energy revolution right now, one that has changed the U.S. energy picture from scarcity to abundance.”

“Fracking is letting the U.S. tap vast oil and natural gas reserves that previously were locked away in shale and other tight-rock formations. Up to 95 percent of natural gas wells drilled in the next decade will require hydraulic fracturing. Hydraulic fracturing also is being used to stimulate new production from older wells.”

Since the turn of the century, oil & gas production in the United States has been increasing steadily, largely thanks to fracking. Today, the US has total energy independence.

Hydraulic fracturing in the US is probably the major reason oil prices have decline over the past two years globally.

What is shale gas?

In this British Geological Survey video, scientists explain what shale gas is using lay terms.