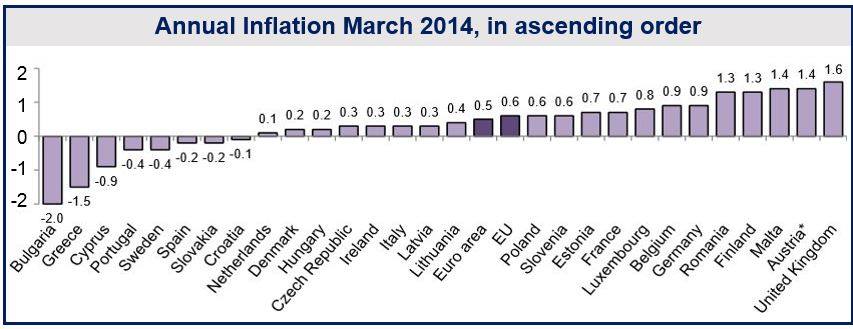

Northern European deflation is creeping in, grabbing Sweden as it joins 7 other EU member states reporting falling prices in March. In Sweden prices fell -4%, Croatia -0.1%, Slovakia and Spain -0.2%, Portugal -0.4%, Cyprus -0.9%, Greece -1.5% and Bulgaria -2.0%.

So far, northern Europe has been relatively free of the economic ills that have affected the “periphery” countries of the European Union (EU). Now that Sweden, a northern European country slides into serious deflation, economists have become jittery.

Several analysts, prominent economists and Swedish politicians are now openly criticizing the Riksbank’s monetary policies. Sveriges Riksbank is the central bank of Sweden and a public authority under the Swedish Parliament (Riksdag).

Swedish authorities were caught by surprise when March’s consumer price fell 0.4%. Immediate action has been urged to prevent a Japanese-style decades-long deflation trap.

It is a great pity, some would say incomprehensible, how Sweden, which first weathered the financial crisis relatively well, and faced none of the enforced constraints of the Eurozone, has managed completely gratuitously to get itself into a deflationary trap.

In Northern Europe, Sweden has slid into deflation and the Netherlands and Denmark are dangerously close. (Source: Eurostat)

Eminent economist blasts Sweden’s central bank

The former deputy governor of the Riksbank and Princeton University professor, Lars Svensson, blasted the central bank for four years of “very dramatic tightening of monetary policy,” which he is certain has caused the slide into deflation.

Prof. Svensson has published many works on deflation and is considered a global authority on the subject. Ben Bernanke, the Chairman of the US Federal Reserve System, sought his advice during the financial crisis.

Large-scale QE needed

Interest rates need to be slashed immediately from 0.75% to (minus) -0.25%, Prof. Svensson said. He urged the Swedish central bank to prepare for “large scale” QE (quantitative easing).

Sweden fell into a liquidity trap in the 1930s, with falling prices which caused debt burdens to rise in real terms, Svensson explained. Sweden is currently knocking on the door of this this liquidity trap, he added. With Swedish household debt among the highest in Europe – 170% of disposable income, rising debt burdens could drive a large number of Swedes into bankruptcy.

The Riksbank has acknowledged that something unexpected had gone seriously wrong. The central bank wrote “Low inflation has not been fully explained by normal correlations between developments in companies’ prices and costs for some time now. Companies have found it difficult to pass on their cost increases to consumers. This could, in turn, be because demand has been weaker than normal.”

Historically, it has not been in the Riksbank’s nature to be over-hawkish. Over the last 100 years Swedish economists have generally been ahead of their times. In fact, John Keynes took many of his more avant-garde ideas from the Stockholm School in the 1920s.

The Netherlands, another northern European country registered a consumer price rise of just 0.1% in March. Dutch inflation has been falling month after month. Many predict price falls in the months to come. A large proportion of the Netherlands’ population are currently trying to manage with loans close to 250% of disposable income. One quarter of Dutch mortgages are in negative equity, and house prices continue to fall. And then there is Denmark with a mere 0.2% March (annual) inflation rate….

Why do debt burdens rise during prolonged deflation?

When consumers know that prices are going to fall (deflation) they postpone their purchases, waiting for better prices. Lower consumer spending means companies sell less and make less money. If companies sell less, they start reducing prices to boost sales, and a vicious circle ensues. Eventually, as prices continue falling, so do wages.

During a prolonged period of deflation wages fall, but the monthly repayments on loans do not, they remain the same, and represent a higher percentage of people’s wages, i.e. there is a higher debt burden.

Bank of England took another direction, thankfully

The Bank of England chose the path of QE and low interest rates, measures that have allowed most Brits to avoid negative equity. While UK house prices have fallen in real terms since the financial crisis hit, the real debt burden has also declined.

The UK’s inflation rate at 1.6% is the highest in the EU, but is still below the Bank of England’s target of 2%. Britain is one of very few European countries with a large safety buffer against an external shock.

March inflation for the EU as a whole dropped to 0.5%, well below the ECB’s (European Central Bank’s) 2% target. After excluding sales tax (VAT) hikes, March’s inflation rate is reduced to 0.3%.

The Telegraph quotes Andrew Roberts, from the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), who said “The RBS “deflation vulnerability indicator” has risen to 80% for Spain, 64% for Ireland, 55% for the Netherlands and 52% for Portugal.”