A supermassive black hole discovered using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory burps after a giant meal of stars and gas – the outburst affects the galactic climate, in other words, the belch from the supermassive black hole affects the landscape of the galaxy in which it resides.

According to NASA, this supermassive black hole is quite near to the Earth – about 26 million light years away – which astronomically-speaking is just around the corner.

Scientists found this outburst (burp) in the supermassive black hole centered in a relatively small galaxy called NGC 5195. It is a ‘companion galaxy’ that is merging with NGC 5194, a large spiral galaxy, also known as ‘The Whirlpool’.

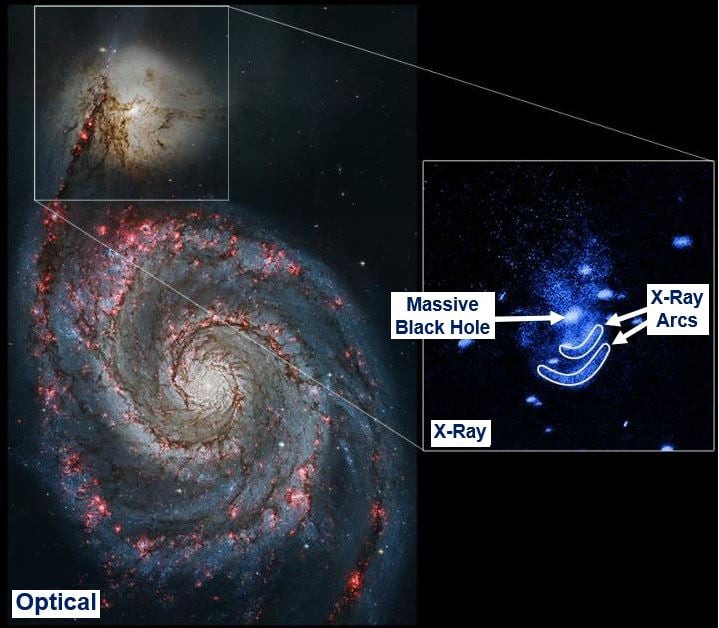

Spiral galaxy NGC 5195 and the X-ray arcs that Schlegel’s team identified. (Image: utsa.edu. Credit: Eric Schlegel)

Spiral galaxy NGC 5195 and the X-ray arcs that Schlegel’s team identified. (Image: utsa.edu. Credit: Eric Schlegel)

It is the first galaxy to be classified as a spiral galaxy. The two galaxies are in the Messier 51 galaxy system.

Black hole belching likely common in early Universe

Study leader, Dr. Eric M. Schlegel, Vaughan Family Professor at The University of Texas in San Antonio, said:

“For an analogy, astronomers often refer to black holes as ‘eating’ stars and gas. Apparently, black holes can also burp after their meal. Our observation is important because this behavior would likely happen very often in the early universe, altering the evolution of galaxies.”

“It is common for big black holes to expel gas outward, but rare to have such a close, resolved view of these events.”

Dr. Schleger and colleagues presented their findings earlier this month at the 227th meeting of the American Astronomical Society meeting in Kissimmee, FL. They also submitted a paper to The Astrophysical Journal.

In the Chandra data, Dr. Schlegel and graduate student in the Fisk-Vanderbilt University physics program, Laura Vega, detected two arcs of X-ray emission near to the center of NGC 5195.

Arcs are probably outburst fossils

Co-author, Prof. Christine Jones, a lecturer in Astronomy at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Mass., said:

“We think these arcs represent fossils from two enormous blasts when the black hole expelled material outward into the galaxy. This activity is likely to have had a big effect on the galactic landscape.”

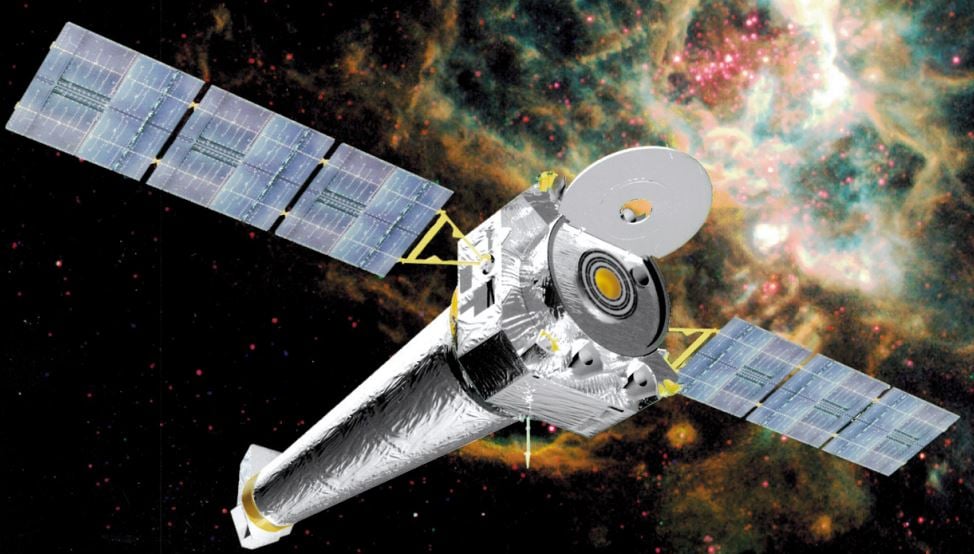

An artist’s illustration of the Chandra spacecraft in orbit. Since its launch on July 23, 1999, the Chandra X-ray Observatory has been NASA’s flagship mission for X-ray astronomy, taking its place in the fleet of ‘Great Observatories.’ It is the most sensitive X-ray telescope ever built. (Image: chadra.harvard.edu)

An artist’s illustration of the Chandra spacecraft in orbit. Since its launch on July 23, 1999, the Chandra X-ray Observatory has been NASA’s flagship mission for X-ray astronomy, taking its place in the fleet of ‘Great Observatories.’ It is the most sensitive X-ray telescope ever built. (Image: chadra.harvard.edu)

Just outside the outer X-ray arc, the scientists detected a slender region of emission of comparatively cool hydrogen gas in an optical image from the Kitt Peak National Observatory 0.9-meter telescope, located on 2,096 m (6,880 ft) Kitt Peak, of the Quinlan Mountains in the Arizona-Sonoran Desert.

This suggests that the hotter, X-ray emitting gas has swept up the hydrogen gas from the galaxy’s centre.

The scientists say this is a clear case in which a supermassive black hole is affecting its host galaxy in a phenomenon they call ‘feedback’.

In NGC 5195, the properties of the gas surrounding the X-ray-glowing arcs suggest that the outer arc has spewed up enough material to initiate the formation of new stars.

Black holes don’t just destroy – they create too

Co-author Marie Machacek, an astrophysicist in the High Energy Astrophysics Division at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, said:

“We think that feedback keeps galaxies from becoming too large. But at the same time, it can be responsible for how some stars form. This shows that black holes can create, not just destroy.”

Prof. Schlegel and colleagues believe the outbursts of the supermassive black hole in NGC 5195 might have been caused by the interaction of this smaller galaxy with its larger spiral companion, causing gas to be funneled in towards the black hole.

The energy generated when this matter fell in would produce the burps (outbursts). The scientists estimate that it took from one to three million years for the inner arc to reach its current position, and from three to six million years for the outer arc.

The arcs are also significant because of where they are in the galaxy. They are located well outside the region where rapid winds (outflow) have been detected from active supermassive black holes elsewhere in other galaxies, yet within the much larger filaments and cavities observed in the hot gas around several massive galaxies.

As such, they could represent a rare view of an intermediate stage during the feedback process operating between the black hole and interstellar gas.

BBC Video – Meet the Supermassive Black Hole Experts