What happens when toddlers talk to voice-activated devices? What happens, for example, when a small child talks to Echo, Alexa, Siri, or Google Assistant, i.e., voice-activated devices?

When adults talk to voice-activated devices, we try to be as clear as possible. We know that it is a nascent technology, and that clarity is vital. If we don’t talk clearly, it might not respond or do what we say.

A toddler, however, stammers, mispronounces words, and pauses. Young children also have their special little words and utterances. After all, they are also beginners.

Sadly, in many cases, the device responds with its default robot apology. In fact, the child may not get any response at all.

Voice-activated technology has become extremely popular. It is a pity it has not managed to reach every family member, say researchers from the University of Washington.

Voice-activated devices and children

Children and adults do not communicate with technology, including voice-activated devices, in the same way.

A more responsive device would be more useful for more people, the researchers suggest. The device could, for example, repeat or prompt the user, especially if the user is a young kid. In other words, it could try to help the user along with prompts and clues, just like a parent might.

Alexis Hiniker and colleagues wrote about the study and findings in the Proceedings of the 17th Interaction Design and Children’s Conference (citation below), which was held in Trondheim, Norway. Hiniker is an assistant professor at the UW Information School.

Other authors on this study were Sijin Chen, a master’s student in the UW Department of Human Centered Design & Engineering; Yeqi Chen, a senior in the UW Department of Electrical Engineering; Kate Yen, who graduated from the UW Department of Sociology; and Yi Cheng, who graduated from the UW Information School.

Voice-activated devices common today

In the United States, nearly 40 million homes have voice-activated devices such as Google Home or Amazon Echo. Last year, Echo Dot and the Fire TV Stick were the best-selling products that US Amazon Prime members purchased.

According to estimates, more than 50% of the country’s household will have a voice-activated device by 2022.

Some interfaces have special features which make it easier for younger people to use them. However, they mostly rely on clear and precise English. In other words, they are only effective when teens and adults use them.

Even teens and adults need to be very specific when interacting with most voice-activated devices.

Accents

If you are not a native English speaker, you may hit some snags with these ‘smart speakers.’ Even native English speakers with regional accents may have a hard time.

Voice-activated devices are conversation partners for kids

For children, voice-activated devices are conversation partners, the researchers observed. Developers should bear this in mind when creating new devices or upgrading existing ones.

Regarding how sellers of voice-activated devices promote their products, Hiniker commented:

“They’re being billed as whole-home assistants, providing a centralized, shared, collaborative experience.”

“Developers should be thinking about the whole family as a design target.”

The study – 14 kids

The researchers recorded fourteen kids aged from three to five. They were with their parents, so their parents’ voices were also recorded.

They played ‘Cookie Monster’s Challenge,’ a Sesame Workshop Game, on a tablet. The researchers had given the participants the tablets.

Child quacks and duck quacks back

In this game, children must ‘quack’ like a duck every time they see a duck waddle across the screen. They do so at random intervals.

When the child ‘quacks,’ the duck on the screen should quack back. However, in this case, the duck appeared to have ‘lost its quack.’

A Sesame Workshop study

The researchers were originally evaluating, on behalf of Sesame Workshop, how various tablet games affected children’s executive function skills. Sesame Workshop funded the study.

However, when Hiniker and colleagues configured the tablet to record the kids’ responses, they later learned that their data-collection tool made the device deaf to the kids. In other words, it shut off the device’s ability to ‘hear’ them.

What the researchers had instead were over 100 recordings of kids attempting to get the duck to respond. They were, in effect, trying to repair a lapse in conversation. Their parents’ efforts to help were also in the recordings.

Hence, a new study was born; one that observed children trying to communicate with non-responsive voice-activated devices.

Children’s communication strategies

Hiniker and colleagues grouped the children’s communication strategies into three categories:

1. Repetition

In 79% of cases, the children used repetition. It was the most common approach.

2. Increased volume (louder)

This strategy involved shouting back at the duck on the screen, i.e., uttering a loud ‘quack.’

3. Variation

The children varied their response through pitch or tone. They also extended the word, i.e., uttering ‘quaaaaack,’ to no avail.

The children were persistent. Without any evidence of frustration, they got the game to work more than seventy-five percent of the time.

Frustration was evident in fewer than one-fourth of the recordings. In only six out of 100 recordings did a child ask an adult for help.

Parents

Parents were happy to help. However, they were also quick to decide that something was wrong and take a break from the game.

In most cases, parents suggested their children try again. Some even took a shot at responding.

The children only agreed to stop trying when they were sure there was something wrong with the game.

According to the researchers, the results represented a series of strategies that families use in real life when a device doesn’t work properly.

The results also gave the team a better understanding of how young children communicate with voice-activated devices.

Can voice-activated devices mimic parents?

Couldn’t we get voice-activated devices to help children like their parents do?

Hiniker explained:

“Adults are good at recognizing what a child wants to say and filling in for the child. A device could also be designed to engage in partial understanding, to help the child go one step further.”

Device could help the child along

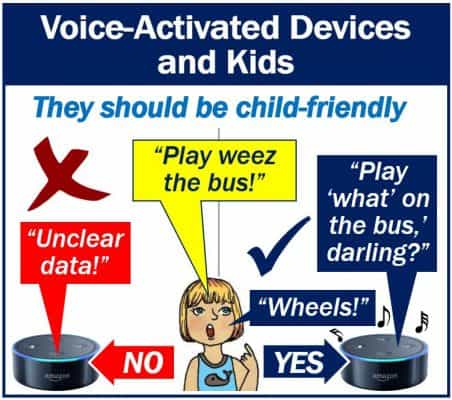

Let’s imagine, for example, that a child wants the device to play ‘Wheels on the Bus.’ If the device did not understand, it could respond with ‘Play What?’ It could also fill in part of the title, which would prompt the child for the rest.

In fact, such a response would also be useful for adults, Hiniker pointed out. Conversations between people are full of tiny mistakes. The future of voice-activated devices must include ways to repair such disfluencies.

Focus on understanding, not just responding

Hiniker added:

“AI is getting more sophisticated all the time, so it’s about how to design these technologies in the first place.”

“Instead of focusing on how to get the response completely right, how could we take a step toward a shared understanding?”

Hiniker is currently studying how diverse, intergenerational families use voice-activated devices. She is also trying to determine what communication needs emerge.

Citation

‘Why doesn’t it work? Voice-driven interfaces and young children’s communication repair strategies,’ Yi Cheng, Kate Yen, Yeqi Chen, Sijin Chen, and Alexis Hiniker. IDC ’18 Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Interaction Design and Children. Pages 337-348, Trondheim, Norway — June 19 – 22, 2018. ISBN: 978-1-4503-5152-2 DOI: 10.1145/3202185.3202749.