You can watch the Transit of Mercury today, 9th May, but make sure you take precautions – you should never look directly at the sun with the naked eye. Your equipment must special filters – which have been approved – fitted onto them, says the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS).

Looking directly at the Sun is extremely dangerous, and can result in permanent damage to the retina, and even blindness, the RAS warns.

The transit of Mercury, which occurs thirteen to fourteen times every century, happens when our Solar System’s smallest planet passes directly between the Earth and the Sun. Mercury is also the nearest planet in our Solar System to the Sun.

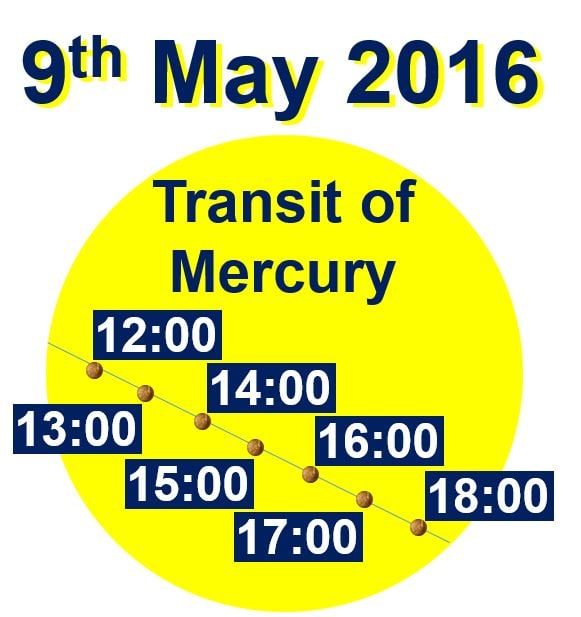

Transit of Mercury. Times are UT (Universal Time), which means the same as GMT (Greenwich Mean Time). According to the Arthur C Clarke Institute: “The telescope must be suitably equipped with adequate filtration to ensure safe solar viewing. The visual and photographic requirements for the transit are identical to those for observing sunspots and partial solar eclipses.”

Transit of Mercury. Times are UT (Universal Time), which means the same as GMT (Greenwich Mean Time). According to the Arthur C Clarke Institute: “The telescope must be suitably equipped with adequate filtration to ensure safe solar viewing. The visual and photographic requirements for the transit are identical to those for observing sunspots and partial solar eclipses.”

Transit of Mercury different from solar eclipse

The transit of Mercury is not the same as when the Moon passes between the Earth and the Sun and day turns into night for some people on Earth.

Mercury is a very small planet, which is much further from the Earth than the Moon. When it passes directly in front of the Sun it appears just as a minuscule dot. During the transit you will not notice any difference in the amount of daylight around you.

The transit of Mercury – a rare occurrence

Every one hundred years there are only 13-to-14 transits – the last one happened in 2006, while the last such event observable in the UK occurred in 2003. After today’s, the next one will take place in 2019, and the one after that in 2032.

There are organised public events – to observe the transit of Mercury – in many parts of the world today, says the Royal Astronomical Society.

There are organised public events – to observe the transit of Mercury – in many parts of the world today, says the Royal Astronomical Society.

People in the Scotland, Northern Ireland and the very northern parts of England should have clear skies today, and will most likely have a good view of the transit. However, the skies will be “Turning cloudier in the south today, with heavy rain at times, perhaps turning thundery later,” according to BBC Weather.

The transit will begin today at 12:12 BST and finish at 19:42 BST. You will observe a silhouetted disk – the planet Mercury – slowly making its way across a very bright solar surface.

Concerning how much of the Sun is blocked by Mercury, the RAS writes:

“Because the planet is so small, it only blocks out a tiny part of the light of the Sun. This means it is impossible to see Mercury, and dangerous to try to observe it with the unaided eye, or using a telescope or binoculars without approved specially designed filters.”

Londoners invited to an RAS event

If you live in London, or within reasonable travelling distance from Piccadilly, you should consider coming to the RAS’ headquarters at Burlington House, London W1J 0BQ, where a special event has been organised in the courtyard.

A team of professionals will be on hand in the courtyard to help operate the telescopes, which have all been fitted with specially-designed solar filters to protect skygazers’ eyes.

The last #mercurytransit was in 2006, and the next one won’t happen until Nov 2019. Do not miss tomorrow #transit pic.twitter.com/ANyawtOQoK

— Space Agenda (@spaceagenda) 8 May 2016

All members of the public, including tourists, are invited to the event, where staff will be there to help from 12:00 until the Sun sets over the surrounding buildings.

An interesting range of astronomical equipment will be set up outside the Royal Academy.

You can watch a live feed of the transit, which will be hosted at the RAS lecture theatre. There will also be a special exhibition of Mercury materials in its library.

Professor Martin Barstow, Pro Vice Chancellor and Head of the College of Science and Engineering at the University of Leicester, and also President of the Royal Astronomical Society, said regarding the Transit of Mercury:

“It is always exciting to see rare astronomical phenomena, such as this transit of Mercury. They show that astronomy is a science that is accessible to everyone, and I would encourage you to take a look if the weather is clear… but do follow the safety advice!”

In 1631, Pierre Gassendi, a French priest and astronomer, saw the transit of Mercury – the first human to do so. (Image: mesnil.saint.denis)

In 1631, Pierre Gassendi, a French priest and astronomer, saw the transit of Mercury – the first human to do so. (Image: mesnil.saint.denis)

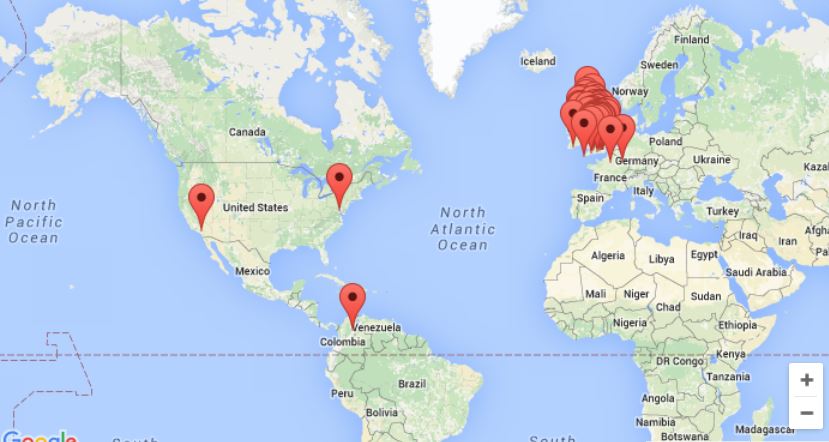

The transit should be observable – if skies are clear – in Northwest and West Africa, most parts of South America, the eastern regions of North America, and Western Europe.

The RAS informed:

“Most of the transit (either ending with sunset or starting at sunrise) will be visible from the rest of North and South America, the eastern half of the Pacific, the rest of Africa and most of Asia. Observers in eastern Asia, south-eastern Asia and Australasia will not be able to see the transit.”

The transits of Mercury are relatively rare events, however, when they do occur they can be viewed from several parts of the world.

Pierre Gassendi (1592-1655), a French astronomer, scientist, priest, philosopher and mathematician, first observed the transit of Mercury in 1631, approximately two decades after the telescope was invented (in the Netherlands).

The area covered in yellow spheres is where people will be able to observe today’s transit of Mercury.

The area covered in yellow spheres is where people will be able to observe today’s transit of Mercury.

Program Manager at the Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA, Louis Mayo, commented:

“Back in 1631, astronomers were only doing visual observations on very small telescopes by today’s standards.”

Over the past nearly four centuries, technology has advanced significantly. Today, astronomers can study the Sun and planetary transits in considerably greater detail.

NASA says the following about the transit of Mercury:

“[The transit of Mercury] is the passage of a planet across the Sun’s bright disk. At this time, the planet can be seen as a small black disk slowly moving in front of the Sun. The orbits of Mercury and Venus lie inside Earth’s orbit, so they are the only planets which can pass between Earth and Sun to produce a transit.”

How did planet Mercury get its name?

Planet Mercury gets its name from the Roman messenger of the gods. In Roman times, most people believed that the gods and goddesses made decisions that controlled all our fates.

He wore winged sandals, a winged cap and carried a caduceus (staff). He also travelled incredibly fast from place to place.

Mercury orbits our Sun once every 88 days, compared to Earth’s 365 days – so Mercury, like the messenger, is also a fast mover.

Transits useful for scientists in the past

Although there is currently no scientific reason for watching the transit of Mercury, centuries ago they helped astronomers with useful scientific information, such as the distance from Earth to the Sun.

By viewing a transit from two different locations on Earth’s surface, one could estimate the distance of Mercury. Then, because the length of each planet’s year is linked to how far it is from the Sun, knowing Mercury’s distance gave us Earth’s distance from the Sun, as well as those of all the other celestial bodies in our Solar System.

The Society for Popular Astronomy makes the following comment about photographing the transit:

“Taking photos through a telescope is quite tricky without the right equipment, so you might have to settle for taking snaps of the projected image or holding your camera up to the eyepiece and hoping for the best.”

“The clever way to do it is to have an adapter that allows you to link to the telescope a camera whose lens you can remove, so you are using it as a big telephoto lens. Cheaper telescopes may not work with adapters, however, so check with your telescope supplier before buying the adapter for your particular camera.”

Video – Transit of Mercury 9 May 2016

This NASA video explains what happens on 9th May, 2016, during the transit of Mercury.