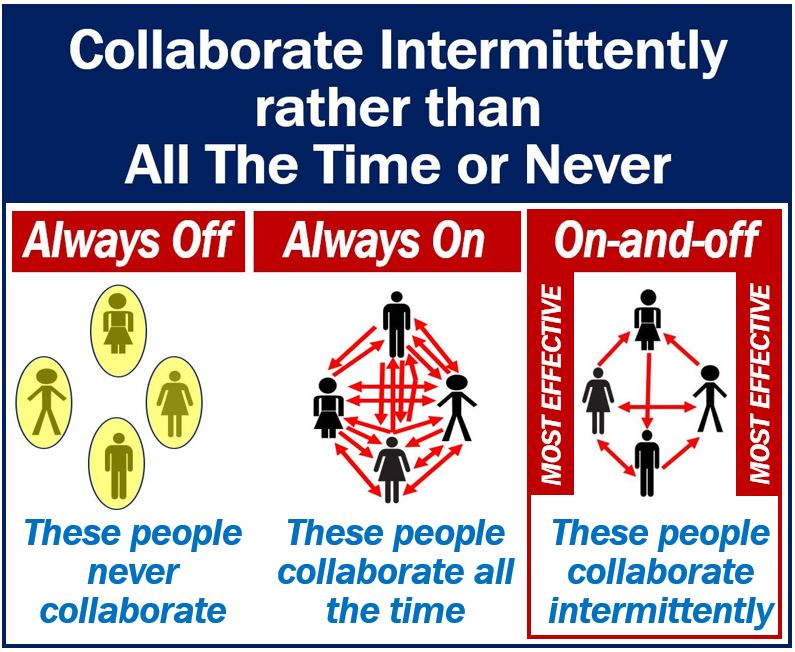

It is better to collaborate intermittently rather than all the time or not at all, three researchers suggest. For complex solving, ‘always on‘ or ‘always off‘ may not be as effective as ‘intermittently on.‘ That is what Ethan Bernstein, Jesse Shore, and David Lazer found in a new study.

The researchers wrote about their study and findings in PNAS (citation below). PNAS stands for Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (of the United States of America).

Smartphones have been around for about a decade. Today, we are awash with ‘always on’ technologies. We have social media, IM, Slack, Yammer, email, Whats App, and so on.

With all that connectivity, we are constantly voicing opinions and sharing answers and knowledge. Surely, that constant brainstorming is great for solving work problems, right?

The authors put together, studied, and analyzed the results of several three-person groups. The groups performed a complex problem-solving task.

Group 1 – always off – never collaborate

In this group, members never interacted with each other. In other words, they tried to solve the problem in complete isolation.

Group 2 – always on – constantly collaborate

In this group, members constantly interacted with each other. This is what most people who have access to always-on technologies do.

Group 3 – on-and-off – collaborate intermittently

Members of this group interacted only intermittently. ‘Intermittently’ means at irregular intervals; not steadily or continuously.

Performance of the three groups

Never collaborate group – the most creative

Previous research had shown that the members of the ‘always off’ group tended to be the most creative.

Members who never interact come up with the highest number of unique solutions. While their ideas are among some of the best solutions, they are also among some of the worst.

People who work in isolation tend to produce the widest range of solutions, previous studies had shown. The findings in this latest study agreed with those of previous ones. In other words, due to the variation, the ‘always off’ group produced a low average quality of solution.

Always collaborate group – better, but not the best

The researchers also expected the ‘always on’ group members to produce a higher-than-average solution.

However, they did not expect them to frequently find the very best solutions. That proved to be the case.

Collaborate intermittently group – the best of both worlds

This last finding surprised the researchers. They found that members in the ‘on-and-off’ group preserved the best of both worlds.

In other words, they had an average quality of solution that was almost the same as that of the ‘always on’ group.

However, by only collaborating intermittently, the ‘on-and-off’ group preserved enough variation to also find some of the best solutions.

High performers learned from low performers

The higher performers were able to improve by learning from the low performers only in the ‘collaborate intermittently’ group. The authors said that this was perhaps the most interesting finding of the study.

A Harvard Business School article says the following regarding high performers learning from low performers:

“When high performers interacted with low performers constantly, there was little to learn from them, because low performers mostly just copied high performers’ solutions and high performers likely ignored them.”

“But when high performers interacted with low performers only intermittently, they were able to learn something from them that helped them achieve even greater solutions to the problem.”

Workplace implications

The researchers see several workplace implications from their findings. There may be advantages, for example, to alternate independent efforts with group work over a specific period. It could be an effective way to get optimal benefits.

In fact, that is how many organizations function. Employees work alone and then get together in a meeting. Subsequently, they work alone again, etc. Employees collaborate intermittently.

However, the constant advancement of technology is breaking these cycles.

Prof. Bernstein said:

“As we replace those sorts of intermittent cycles with always-on technologies, we might be diminishing our capacity to solve problems well.”

Sprints and hackathons

The authors see parallels today in several trends in organizations. Agile approaches to teamwork have some of these intermittent traits. Teams are organized, for example, into ‘sprints,’ i.e., gatherings of members that focus on something and last only a short time.

Similarly, hackathons provide some intermittency of interaction. A hackathon is an event in which many people meet to engage in collaborative computer programming. Hackathon events typically last a few days.

Organizations that are famous for their brainstorming ideas and excellence in creativity use a process in which participants collaborate intermittently. IDEO, for example, uses a process that has intermittency built in.

Even open offices have some group spaces such as meeting rooms and booths. They also have individual spaces, such as pods in which interaction may be temporarily paused.

These design-based tools that make participants collaborate intermittently rather than constantly are extremely important for organizational productivity. Given their findings, the authors believe they are more important than previously thought.

Productivity, in this context, refers to how much each unit of input produces in a given period. For example, how many units of a product a worker produces per hour, day, week, month, etc.

The authors warn:

“The march towards always-on technology – and more and more digital collaboration tools at work—should not disturb the intermittent isolation that those practices bring, lest it keep groups from achieving their best collective performance in solving complex problems.”

Citation

“How intermittent breaks in interaction improve collective intelligence,” Ethan Bernstein, Jesse Shore, and David Lazer. PNAS August 13, 2018. 201802407; published ahead of print August 13, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1802407115.

The authors

Ethan Bernstein is an Associate Professor in the Organizational Behavior unit at the Harvard Business School.

Jessie Shore is an Assistant Professor of Information Systems at the Questrom School of Business, Boston University.

David Lazer is a Professor of Political Science and Computer and Information Science in the Department of Political Science and the College of Computer and Information Science, Northeastern University.